"A DREAM BAND"

by Christopher Popa

December 2004

Meanwhile, Thomas voiced skepticism about his own joining the orchestra.

"Actually, I didn't even think I would be in it," he said. "I had worked with him when I was 18 years old, up in Boston, in 1938 . . . I subbed when a trumpet player friend's wife had died. He was a friend of mine, and when Glenn got ready to pay me, I didn't take any money. I wouldn't take any money, and I think that made an impression on him. Later on

(I didn't see Glenn for five years), he had me transferred out of the Field Artillery. And then I still thought I might be playing with just a post band or something. I got there at 11 o'clock and we did the first broadcast at 1 o'clock, and I did every broadcast, every record, every whatever, 'til 1945 when I got out of the service."

With his years and years of experience, Leyden knows who to seek out when he conducts tributes to Miller or the big bands across the country.

"Well, I work with a contractor every place I go - somebody who's experienced and knows the people who will play the kind of style I'm looking for," he said. "There's a broad spectrum: some of them are young and some of them are quite old. I always feel more comfortable if I see some gray hair. I can tell from the way they're warming up."

So what can he reasonably expect, beyond the correct notes?

"Well, it's a short term thing," he explained. "You just got to realize that two days from now, you're going to be doing concerts. And then you won't see these guys again for another year. They've been extremely cooperative, and this year... last year, one guy kind of turned me off and so I didn't hire him this year."

Leyden has a lot of Miller music from which to choose.

"I don't pick anything from the Air Force," he cautioned. "I do it if I have the forces, like a string section. If I don't have a string section, I just go with the old tunes - there's plenty of them! Because that's what people remember, they don't remember the Air Force band, unless they were just a certain age or during the war. The earlier ones, the old standards, are still viable now. I can't play a concert without doing String of Pearls and In the Mood."

What would happen if he included something like Now I Know or Time Alone Will Tell?

"They would say that sounds wonderful, but it doesn't have any memories for me," he reasoned. "The only one I've ever done in concert here was Long Ago (And Far Away), but I did have the [Oregon] Symphony to work with, where I could have all the strings I wanted. When I go out on the road, I'll just get 17 players."

It's simply too expensive to routinely use a string section.

"Oh yeah, Glenn got in when the price was right," he joked.

Who's coming to Leyden's programs in 2004?

"Well, mostly Glenn Miller fans of an age. Probably most are over 50," he reported.

Enough under 50 to keep the big bands going?

"I don't think so, if you want to know," he answered.

Admittedly, no one can do anything with rap or hip-hop songs, but why did it seem easy, during the '60s or '70s, to arrange certain newer pop songs, such as The Way We Were, in the Miller style?

"That was a retro ballad, from the old days," he explained. "Same way with Henry Mancini - Days of Wine and Roses or Moon River, you could have made into... they have, from a strictly theoretical point, they've got an interesting harmony and a sentimental song of words, neither of which reflect today's culture. So it was all a part of that period - the wartime and romance. It was also the super composers that we had, writing those... people like Johnny Mercer... writing those words. That's why they're still being played today . . . great stuff with great writers, and there aren't any great writers, the whole thing has disappeared 'cause everybody writes their own tunes. That's another thing to talk about, it's not part of my world."

So Leyden returned to discussing Miller.

"I don't know what he would have done after the war," he admitted, "but he did have some plans to settle in California and to have a string section. It probably would have been exciting to see how that could develop from where it was. But I would say his management of the band and, musically, his personnel and just business-wise, was exemplary. He was very successful in all counts."

"I looked forward to every note I blew in there," Thomas said. "You did your best, 'cause you knew it was good. You had the best players in the country, you had the best arrangers . . . Lord knows, that sax section with Miller will sound good a thousand years from now. He had a helluva impact. I'd like to come back in a thousand years, I bet they're still playing Glenn Miller."

see also - "Feedback and Follow-Up" Re: Glenn Miller

Today, Leyden continues to perform across the nation, conducting tributes to Miller in such major cities as Minneapolis and Indianapolis, and speaking about his one-time boss at Colorado University at Boulder.

"You've been spying on me, 'eh?," he kidded. "You probably have Internet connections. People always surprise me and say, 'Well, I hear you were in Minneapolis last week.' I don't have the Internet, that's why I look so illiterate."

Recreating Miller music, with integrity and authenticity, is not an easy task.

"My job, as I figure it now, is I'm practically the last of the Mohicans - somebody actually doing concerts like this, at least with first-hand experience. So my job is to get it as accurate as I can, so I try and be as strict as I can," Leyden confided. "I don't get any problems with the good guys who play, they like to do it... they like to do it right. But you're working with other people and no matter what you do, you don't have the same personnel, and that's part of the sound, too, especially in the civilian band. He never got the sound with his service band, 'cause with Peanuts [Hucko] playing lead, instead of Willie Schwartz, it was just a different combination of instruments. There were none of the saxophone players there, that were in his other band. It really never came close."

Glenn Miller's proposal:

"For the past three or four years my orchestra has enjoyed phenomenal popularity until we have now reached a point where our weekly gross income ranges from $15,000 to $20,000. Needless to say, this has been and is most profitable to me personally but I am wondering if it would not be more in order at this time for me to be bending my efforts toward the continuance of this income if it could be devoted to USO purposes, the Army Relief Fund or some other approved purpose. If, by means of a series of benefit performances or other approved methods, even some part of this income could be maintained and used for the improvement of army morale I would be entirely willing to forego it for the duration. At the same time, by appropriate planning, programs could be regularly broadcast to the men in the service and I have an idea that such programs might put a little more spring into the feet of our marching men and a little more joy into their hearts."

- letter to Brigadier-General Charles D. Young, Aug. 12, 1942

It's hard to imagine what Glenn Miller would make of the continuing interest today in his music.

"I don't know," Norman Leyden, one of the arrangers with Miller's Army Air Force band, said to me in 2004. "He wasn't a very good conversationalist. He never spoke out on matters like that."

But it was easy to see Miller was proud of his band.

"Well, just by keeping a tight rein on things, I guess, and making sure that it was always playing up to snuff," Leyden observed.

recommended listening - select list:

It Must Be Jelly ('Cause Jam Don't Shake Like That)

George Williams, arranger (Mar. 11, 1944, broadcast)

Holiday for Strings Jerry Gray, arranger (Apr. 1, 1944, broadcast)

Peggy the Pin-up Girl Ray McKinley and The Crew Chiefs, vocal

(Apr. 29, 1944, broadcast)

Poinciana (Song of the Tree) Johnny Desmond, The Crew Chiefs, vocal /

Jerry Gray, arranger (Apr. 8, 1944, broadcast)

Everybody Loves My Baby (But My Baby Don't Love

Nobody But Me) Jerry Gray, arranger (May 19, 1944, broadcast)

Join the Wac [Women's Army Corps] Crew Chiefs, vocal

(Apr. 8, 1944, broadcast)

St. Louis Blues March Ray McKinley, Perry Burgett, and Jerry Gray, arrs.

(Oct. 29, 1943, V-Disc)

Jeep Jockey Jump Jerry Gray, arranger (Feb. 12, 1944, broadcast)

What Do You Do in the Infantry The Crew Chiefs, vocal

(Feb. 26, 1944, broadcast)

Flying Home Steve Steck, arranger (Apr. 8, 1944, broadcast)

Irresistible You Johnny Desmond and The Crew Chiefs, vocal

(Jun. 2, 1944, broadcast)

(There'll Be a) Hot Time in the Town of Berlin

Ray McKinley and The Crew Chiefs, vocal / Jerry Gray, arranger

(Apr. 22, 1944, broadcast)

Long Ago (And Far Away) Johnny Desmond, voc. / Norman Leyden, arr.

(Mar. 25, 1944, broadcast)

Anvil Chorus Jerry Gray, arranger (Mar. 18, 1944, broadcast)

GLENN MILLER

"I think all of us in the band were proud of it," Whitey Thomas, one of the trumpeters in the Miller service orchestra told me, "because . . . it wasn't money. I think it was just for pride that it sounded as good as it did."

"Proud and conceited are two different things," he continued. "I'm trying to define it for you. It wasn't conceit, it didn't make you feel superior. You knew it was good. And actually, I appreciate it more today, when I listen to it."

To staff his band unit, Miller had his pick of many of the best musicians who had just entered the service.

As Leyden explained, "Glenn would tell a lot of them, 'When you get your draft notice, give me a call and I'll see if I can help you.' And he did help a lot of guys get placed in the band, after their basic training."

He still seems amused that he, too, wound up joining Miller.

"It was just a fluke," he claimed. "It was just a matter of being in the right place, with the right background, at the right time. It has to go back when I first heard the band and started to imitate the style. I've got a recording of a chart they did back in 1939, which I recorded . . . cut it in with a stylus, and I play it now to show people that I was thinking about Miller in those days, where he used the clarinet lead and all, so that I followed the band and followed the arrangements but didn't try to openly ape the same arrangements, but to get the same colors, using the same combination of instruments and all."

Was he was one of those who complained that the Miller band then didn't swing?

"Oh, this is a snobbish group," he shot back. "It didn't swing like Count Basie, no, it wasn't loose like that. But it swung good enough for the public. And the people that criticize it are usually dyed-in-the-wool jazz fans who like the really... Glenn did not profess to be a jazz band. He just had some guys that could play pretty good jazz, like Billy May and some of the others, Al Klink... He obviously favored people whose playing was entertaining, rather than it was really 'the last word in swing.'"

Leyden joined the National Guard in 1940 (supposedly for a year's volunteer duty), but served longer after the Japanese attack on Hawaii. He was first sent to a camp in Jacksonville, FL, then in the fall of 1942 went to a basic training center in Atlantic City, and was promoted to M/Sgt.

Miller happened to stay in Atlantic City for a few weeks.

"He had a chance to hear some of the things I'd done and he gave me a nice, left-handed compliment one time," Leyden recalled. "After a rehearsal, he'd said, 'For a Yale man, you don't play bad tenor [laughs]. I took that for what it was worth, whatever it was worth.'"

"Rehearsing with the guy was such a great experience," he noted. "Because I heard these arrangements, it was really a thrill to play his own charts with him directing it. I saw how fussy he was at that time to get it just right. I'd seen it once before, in civilian life, accidentally, when some friends stopped in at [the] Meadowbrook, where we found the band was playing there on a Saturday afternoon... not only playing, but they were rehearsing when we stopped by. And I caught a rehearsal, it was Sunrise Serenade. And I saw it there, too, how fastidious he was and how insistent and dogged he was at getting the guys to repeat phrases. So I had a little idea about what a strict authoritarian he was about his own style and stuff."

Can you be a nice guy and still have a good band?

"I don't know anybody who's completely nice," he responded. "I look at Fred Waring, who was a tyrant. Benny Goodman with his famous 'ray.' I don't know about Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey. I guess you have to have a sense of authority. You don't have to really come down strong all the time, but... You see, when he was with his civilian band, he was paying pretty good money, so that was really the reason a lot of them hung on. A guy like Al Klink is on record as not liking him, but was one of his best players. During those few years that he had the Chesterfield show and all those best jobs in the country, it was a goal - a well-paid goal. And you didn't have to like the band even."

One day in 1943, Miller and Leyden talked while at dinner together.

"We had a nice chat about business and all," Leyden recalled, "and I questioned, 'Why do you have your arrangers work on such dumb songs as Three Little Fishies (Itty Bitty Poo). He gave me a little talk about the business aspect of repertory and you gotta play what your customers want. But, of course, when he did dumb songs like that, he at least had some kind of humorous arrangements."

Though both men moved on (Leyden wound up in North Carolina), Glenn called him around September 1943 when the Army was planning "Winged Victory," a big musical play on Broadway with an all-service cast, and invited him to conduct the show.

"It was such a stroke of lightning there that hit me," Leyden said. "This job was just laid in my lap, and to this day, I'm not sure what went on in his mind between the time he left Atlantic City and the time he called me from New York."

What had Miller himself been working on, in the meantime?

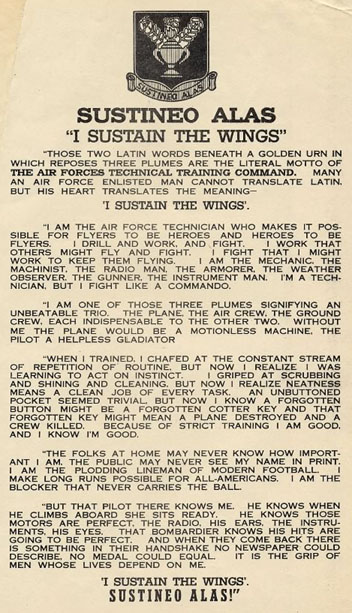

"Glenn, at that time, had gone up to Yale University to settle in there, and really to organize the band he was dreaming about," Leyden explained. "And so he started this 'I Sustain the Wings' program and the band was coming to New York every Saturday to do their show . . . I guess they were traveling all around, doing bond drives in-between."

"Winged Victory" opened that November, and since the programs were done only a few blocks away from each other in New York City, Leyden and others would often attend Miller's rehearsals, stay and see the show, and then go back to the theater and do their own evening performance.

"At one of those times," Leyden told me, "I went up to him and said, 'Captain, the show is going great and I've got some time on my hands. Would you be interested... I'd like to write something for you."

sources:

Polic, Edward F. The Glenn Miller Army Air Force

Band: Sustineo Alas / I Sustain the Wings

(Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.,

1989).

Popa, Christopher. Interview with Norman Leyden,

Aug. 16, 2004.

---. Interview with Whitey Thomas, Aug. 15, 2004.

send feedback about either sketch via e-mail

return to Biographical Sketches index

go to Big Band Library homepage

Would Miller assign songs for Leyden to arrange, or would Leyden come up with tunes to do?

"Worked both ways," he answered. "At the beginning, all I did were suggestions from him, for the first half-dozen or so, before I was really officially with the band. I would bring a chart in and he would give me another tune to do, but he never said anything about what to do with it."

Although it's been some 60 years, Leyden can still identify the first tunes he arranged for Miller.

"Of course!" he exclaimed. "They're all very important steps in my life, as I look back at it. The first one was a tune called Now I Know . . . in a couple weeks, he put it on the air and I noticed that he had made some changes in it, which I thought were kinda good. So after that vote of confidence, he gave me another tune to do . . . Time Alone Will Tell. And he put that one on the air. And the third one was the charm, I think, for me, career-wise. It was Long Ago (And Far Away)."

Leyden also arranged such titles as Going My Way, I Couldn't Sleep a Wink Last Night, and All I Do Is Dream of You, as well as I Sustain the Wings, the opening theme to the AAF band's radio show.

"I arranged for the strings and I arranged for... most of the work was ballads, to be sure, with vocals in them, but that's what I like to do best. And I think I'm more tempermentally suited to that type of repertoire anyways.

Several others arranged for Miller in the service, including Jerry Gray, Ralph Wilkinson, Mel Powell, and Steve Steck.

"Well, Jerry of course was the one with the most experience," Leyden pointed out. "He was the most able to do any kind of job - ballads, swing, special production arrangements - he could do it all, because he worked with Shaw before Glenn (and a lot of other bands, too, I'm sure). He was just extremely experienced, extremely competent, extremely fast. Ralph Wilkinson was quite a different kind of a guy. He was very experienced in classical music and was a staff arranger for [the] 'Telephone Hour,' and brought a sense of classicism to all his arrangements. He would do an arrangement of Laura and it would sound like Ravel wrote it. He just had that extra knowledge of, particularly impressionistic, harmony. And other guys had their specialties. Of course, Mel Powell did his piano stuff and an occasional Goodman-type arrangement. Steve Steck, a trumpeter, who wrote for Ray McKinley and that ['Swing Shift'] band without the strings. Then there were a couple of guys that did vocal stuff, in The Crew Chiefs, and wrote their own parts. Jerry, or whoever was doing the arrangement, would incorporate their parts into their chart."

"For me," he offered, "[Miller's] greatest asset to the band was not as an arranger or even a conductor, but more of an editor of everybody else's work. He knew... I don't think anybody ever brought an arrangement to the band that he didn't do something with, fiddle around with it and make some changes and make it better than it was . . . change a mute or change a little phrase or something."

Leyden told me that Miller altered them for the better.

"Well, I have to agree with the things he did to mine," he said. "'Cause I was a young arranger and I probably wrote too many notes. As a matter of fact, one time in England, I wrote a chart and brought it into rehearsal and I thought it was the 'cat's meow.' But it didn't go over too well, nobody said at the end of it 'Yay!' or stomped the floor. He took me aside after it and said, 'Hey Norm, it was a nice try. But remember it ain't what you write, it's what you don't write.'"

After Pearl Harbor was bombed on Dec. 7, 1941, American men and women were dragged into World War II. Miller wanted to be involved in keeping their spirits up, and hoped to bring his entertaining music right to the troops, whether at their training camps, bases and stations in the U.S. and England or, eventually, closer to the battlefield, with broadcasts to or live appearances on the continent.

"In the big, overall picture, bands were important for morale," Leyden explained. "And to have the number-one bandleader in the country suddenly show up with his own hand-picked band was really kind of exciting, especially if you were the recipient of some of this music that you've been listening to at home and now you're over in Europe some place and your musical idol shows up right on your flying field or in your camp, it was a taste of home."

It made Miller himself happy, too.

"He was dedicated to his ideas, and he had the talent to follow up on them," Thomas reminisced. "And he had an uncanny ability to pick the personnel. A lot of times in a quartet, nobody gets along. But we had 47 guys on the stage."

"He saw his dreams come true, just as long as he lived," Leyden said. "He did put together what people still call the best band of its type. But it was his own thing. He shouldn't be compared with Benny Goodman or Tommy Dorsey or anything like that. He had his own style and his just happened to be so popular that it lasted longer than any of the others."

Even after Miller's disappearance, the band continued to play for Allied personnel, touring Germany during late spring and early summer 1945 and, for example, performing a memorable 2-hour concert at Nuremburg Stadium on July 1st.

"Close to 50,000 G.I.s there," Thomas recalled. "When we hit Moonlight Serenade, we could hear those kids screaming. I looked around and every guy in the band had tears in his eyes. So you can't buy that, man, you got to do it."

"That's the way it was," Leyden confirmed. "It was really exciting for the guys and so they did think highly of the morale-boosting effect of it."

Glenn Miller AAF Band chronology - select events:

Oct. 7, 1942 - Miller reported for duty with Army Specialist Corps (later dissolved into

Army).

Mar. 20, 1943 - The 418th AAF Band (aka, "Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band"), activated

at Yale University, New Haven, CT. (Band unit later known by other designations.)

Jun. 29, 1944 - Band arrived in London.

Jul. 24, 1944 - Miller promoted from Captain to Major.

Dec. 23, 1944 - Telegram informed Helen Miller that her husband was "missing."

Aug. 12, 1945 - Band arrived in New York City.

Nov. 17, 1945 - Final performance of the band, "I Sustain the Wings" broadcast, from

Bolling Field, Washington, D.C.

One story Thomas shared with me happened while the band was stationed at Yale University, during the winter of 1943; he and fellow trumpeter Bernie Privin were sitting in a local bar, around closing time.

"It was during the time when he was getting bad-mouthed from the powers-that-be because we were jazzing up the marches, you know, conventional marches," he recalled, "and Glenn came in with Major Healey. He'd been drinking and all of a sudden he decided he'd go see Zeke Zarchy. Zarchy had some kind of fungus in his feet. They actually thought they were going to have to cut them off; they had scabbed over. He couldn't... we used four trumpets there for about two months. Anyhow, he was in the hospital, and Glenn loved Zeke 'cause he was a helluva trumpet player and he had a lot of respect for him. So, tongue-in-cheek, he never ordered us but he 'ordered' us -- he thought it was funny -- he ordered Bernie and me to go with him and Major Healey to the hospital and take Zeke some chow mein. Now we're talking about it's after 12 o'clock at night. So we go get two quarts of chow mein; you used to get it in quart containers. Chow mein is a greasy, liquid mess, really. Anyhow, we get two quarts of that and we go see Zeke. We get there and the orderly of the day said, 'You can't come in, it's too late.' That's when Glenn bad-mouthed him and ordered him to shut-up . . . We get in the room and Glenn gets the top of off one and the other one's cradled in his arms and he's pulling at the top. When it gives, both quarts go flying across the room. We've got all this chow mein all over the floor. We were in a G.I. hospital with slick concrete, shiny, slick... helluva mess. Now he's got to go back and kiss this guy's ass that he just ordered to leave us alone. And get a mop and all to try to clean it up. Anyhow, to make a long story short, he says to me, 'Why in the hell did you let me act like a horse's ass like that?' I said, 'You've got all the power, Captain. You were ordering everybody around.' He said, 'They told me if I pull that crap again, they're going to bust my ass back to Lieutenant.'"

Admittedly, that's not a very complimentary memory of Miller.

"I'm just trying to humanize him a little bit," he reminded me. "He was quiet. I don't remember ever hearing him laugh real hard. He was an Iowa farm boy."

How about an example of a good personal quality?

"There was no aloofness about Glenn," he observed. "One day my mother and my aunt and her sister came up to the Vanderbilt Theatre in New York, where we were rehearsing. We had to take about a twenty-minute . . . [break] . . . and he spent his whole twenty minutes just talking to my mom, which is unusual. He'd usually just say 'Hello, nice to meet you.' He was just that kind of guy."

Did the age difference between Miller and his musicians ever cause problems?

"No, like when he made Major, he had a big party for the band. And the first year at Yale, the anniversary, he threw a big party for the band," he recalled. "Glenn was good at picking personnel. There was no friction in the band."

How would Thomas, who continued playing professionally until about 1962, describe the trumpet section?

"I sat next to Zeke most of the time," he said. "I would relieve Zeke on some of those

ball-breakers like Anvil Chorus, I Hear You Screamin', Volga Boatmen, things like that . . . Bernie played most of the jazz . . . Bobby [Nichols], he played quite a bit, but not as much as Bernie. I was a utility man. The only jazz score I played was on Caribbean Clipper. I begged Glenn to give it to Bernie. I said, 'I'm no jazzman.' He said, 'Oh, shut up. You ought to hear the shit I've heard come out of those eight bars [laughs].' He said, 'You're doing fine. Keep doing it.' Jazz I can play, but I play around the melody. I'm not trying to thrill anybody. Jack Steele was kind of stationary. He played 3rd or something."

In 1955, just over a decade after Miller's disappearance, RCA Victor released a deluxe 5-record set of the Army Air Force Band's music.

Leyden recalled, "Well, it didn't mean anything to me, financially, except that, after 10 years, when it did come out, I was already in freelance arranging and I was writing any style you want. As long as the phone rang, I was ready to go. But it was nice to have as that sample of our work together. The band still sounds great when you play those things."

In 2001, it was marketed, with additional performances, on compact disc, and Leyden has that, too.

"Of course," he chuckled. "I've got loads of stuff."

Thomas also remembers the release of the AAF set by RCA, and nowadays often listens to those recordings.

"I play one about every day," he stated.

In 1959, singer Johnny Desmond reunited with Leyden and a number of AAF musicians, to record Symphony, I'll Walk Alone, Amor

and other songs in high-fidelity for a Columbia album, "Once Upon a Time."

"It was pretty close because we actually had a lot of the guys doing it," Leyden said, "so certain sounds were pretty close. Some of them were new arrangements and some of them were stuff we had done before. I'm glad that I was able to re-do some of those things, with Johnny."

Among the men in the studio band were Bobby Nichols (tp), Hank Freeman (as), Mannie Thaler (bari), Joe Kowalewski (vln), and Frank Ippolito (d).