ZIGGY ELMAN

"Fralich in Swing"

by Christopher Popa November 2005

The public voted him their favorite trumpeter in quite a number of Down Beat

and Metronome polls. But it wasn't until

several years afterwards that his own son, Martin, understood how special Ziggy Elman was.

"It started when I was about 11 or 12, I really started noticing it, you know, who he really was," Martin told me. "We'd go to Vegas for 10 or 12-week shows with Mickey Katz. We'd stay up there all summer."

Had his friends at school realized who his father was?

"A lot of the teachers did," Martin said. "Not many schoolmates... The people on my street did."

"Oh, it was great," Martin Elman recalled. "Bernardi was a good friend of my father's, and that was very nice . . . I know it's down in the garage somewhere."

An even bigger recognition was given February 24th, 1987, when Elman was posthumously honored with a Grammy Award, for his solo on Goodman's recording of And the Angels Sing.

"It's amazing how they give things to people after they're dead," Martin remarked.

In 2003, historian David French wrote an excellent, in-depth article about Elman in the jazz and ragtime publication Mississippi Rag.

"It was very interesting because . . . he knows so much more about my family than I do," Martin said. "He knows things I don't even know about. This guy researches everything. He's so thorough. He knows everything about my father's life. I mean, he's interviewed people who have played with him. He just seems to have a tremendous amount of knowledge."

As our talk concluded, I gave Martin the opportunity for the last words here, about how his father should be remembered.

"How great he was," he said. "And still, when the name comes up, older people seem to recognize it . . . Well, Carnegie Hall... And the Angels Sing... That's just how great he really was."

sources:

Bernardi, Noni. Interview with the author, Apr. 16, 2005.

Connor, D. Russell. Benny Goodman: Listen to His Legacy (Metuchen, NJ: The

Scarecrow Press, Inc. and the Institute of Jazz Studies, 1988).

"Dorsey Troubles," Down Beat, May 2, 1957, p.10.

Elman, Martin. Interview with the author, Apr. 16, 2005.

French, David. "King of the Sidemen," Mississippi Rag, May 2003.

Garrod, Charles. Ziggy Elman and His Orchestra (Zephryhills, FL: Joyce Record Club,

1990).

Garrod, Charles with Walter Scott and Frank Green. Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra,

Volume Two 1946 - 1956 (Zephryhills, FL: Joyce Music, [ n.d. ]).

"Zagging with Zig," Down Beat, Nov. 9, 1961, p.12.

send feedback about "Ziggy Elman: Fralich in Swing" via e-mail

return to the Biographical Sketches directory

go to the Big Band Library homepage

Elman was a sideman in groups led by Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey, then later led his own big band. So which did he prefer?

"Geez, I really don't know. I never was asked that," Martin said. "I think he always wanted to be on his own."

vital stats:

given name: Harry Aaron

Finkelman

birth: May 26, 1914,

Philadelphia, PA

death: June 26, 1968,

Van Nuys, CA, liver failure

father: Alek Finkelman, a

candy store owner, part-time

cantor, and klezmer violinist;

later, a building contractor

mother: Mina Finkelman

heritage: Russian-Jewish

wife: Blanche Finkelman,

m.Oct. 10, 1937; Ruby

Frances Elman, b.1921,

m.1943, d.1966

son: Martin J., b.1940

His family settled in Atlantic City, NJ in 1918, where he attended school and learned to play trombone, clarinet, saxophone, and trumpet (!).

"Oh, he could play almost every instrument," Martin reported.

It would be with the trumpet, however, that he made a lasting place for himself in music.

"Trumpet," Martin repeated, "but he started out with a violin. His father wanted him to play the violin, but he didn't seem to be interested as much as the trumpet."

Elman had his musicians' card by the time he was 15, and performed in Jewish wedding bands, various dance and jazz groups, and nightclubs.

"He was a very shy person, so being up front was very hard for him," Martin continued. "He didn't seem comfortable being one-on-one with anybody. I remember him doing shows with Jerry Colonna, which were live at that point. And Jerry Colonna would bring him up front, and he seemed to be very shy."

Elman preferred to speak through his horn.

"Yes, correct," Martin said.

Where did the name "Ziggy" come from?

"I think he took it from Ziegfeld," Martin responded.

Florenz Ziegfeld (1869–1932) was a Jewish-American impresario who created a series of theatrical spectaculars, called "the Ziegfeld Follies."

Elman evidently enjoyed spending his breaks at work surrounded by chorus girls, so the moniker seemed to fit.

As for the last name "Elman," it was a shortened version of Finkelman.

In 1932, he joined Alex Bartha's band, which made some recordings for Victor, featuring him on trombone. Bartha's orchestra also was hired to play the Steel Pier in Atlantic City, where Elman began concentrating on trumpet.

Elman's trumpet was joyous, unrestrained, and... loud.

"Very loud, yeah," Martin agreed.

His tone was clear and enunciated.

"It was very sharp. When I listen to the radio, I can pick it out," Martin said.

And it caught Benny Goodman's attention. Goodman offered Elman a job in September 1936. Harry James

[ shown, l. ] joined Goodman in January 1937 and, with Elman [ middle ] and the third trumpeter, Chris Griffin [ r. ], they became known for their collective ferocity and were nicknamed "The Biting Brass."

In December 1938, Elman was invited to start making some recordings which would be released as "Ziggy Elman and His Orchestra," but, in truth, his musicians

were actually all members of the Goodman band.

"Ziggy got a contract to do 20 sides for Bluebird," saxophonist Ernani "Noni" Bernardi, who was also on the sessions, told me. "And I did all the arrangements for him."

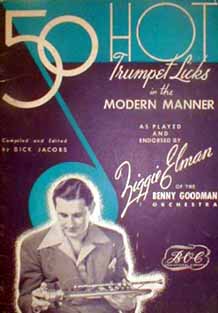

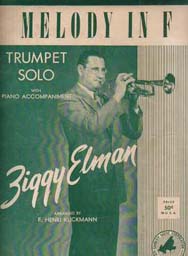

The tunes included Fralich in Swing, which was Elman's Jewish version of a Romanian song called Der Shtiler Bulgar, and Zaggin' with Zig, which Bernardi composed.

Regarding the latter, Bernardi said, "I think Ziggy and the company got that title. I had nothing to do with the title . . . Well, I was pretty satisfied with them, all in all."

recommended solos - select list:

Bugle Call Rag Benny Goodman Victor, 1936

Fralich in Swing Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1938

Bublitchki Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1938

You're Mine, You Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Let's Face in Love Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Zaggin' with Zig Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Am I Blue? Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

What Used to Was Used to Was

(Now It Ain't) Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Deep Night Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Forgive My Heart (You Are My

Happiness) Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Tootin' My Baby Back Home

Ziggy Elman Bluebird, 1939

Hallelujah Tommy Dorsey Victor, 1941

Well, Git It! Tommy Dorsey Victor, 1942

Zaggin' with Zig Ziggy Elman MGM, 1947

King Porter Stomp Jess Stacy

Atlantic, 1954

Goodman had arranger Jimmy Mundy write a full band chart on Fralich in Swing, featuring Ziggy's trumpet and vocalist Martha Tilton, with lyrics added by Johnny Mercer. Renamed And the Angels Sing, it became a #1 hit in 1939, and further solidified Elman's name before the public.

He remained with Goodman until July 1940, when Benny took a hiatus.

Elman played a month with violinist Joe Venuti's band, then joined Tommy Dorsey's orchestra in August, at a salary of $500 a week (other players might have been getting, say, $100). But he also had some extra responsibility, and became Tommy's right-hand man, acting as "straw-boss," conducting rehearsals, filling in as director when Dorsey was momentarily off the bandstand during the course of a night, or, just for fun, when Tommy would play trumpet and Elman would play trombone.

"Most of the time, he did lead the Tommy Dorsey band," Martin said, "'cause Tommy was drinking a lot."

Everyone in Dorsey's band had to play their best.

"Being in the big bands, they did shows all night, you know," Martin said. "They'd get off at 2 in the morning and come back the next day and do it again."

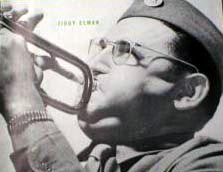

Elman served in World War II beginning in 1943, and was given musical duties.

"Yes," Martin confirmed. "He was drafted, I believe . . . It was the Army Air Force then."

He became a Sargeant, and was put in charge of a service band in California.

"He was stationed in Long Beach," Martin explained. "The big wigs sent him, basically, all over the country, playing for different shows, [ as ] entertainment with the Army band."

Elman was discharged in February 1946, but didn't immediately form his own band.

"No, I think he went back with Tommy for awhile," Martin said. "He was a very close [ friend ] of [trumpeter George ] Seaberg . . . We spent a lot of time with George."

In January 1947, Elman hit the road with his own band.

"I think, deep down, he always wanted his own," Martin commented.

They were signed to the MGM record label, and toured across Pennsylvania and into Ohio with little success, so Elman folded the band and, on May 17, 1947, went back to Dorsey for a year. (To fulfill three remaining 1947 record dates at MGM, he actually used members of Tommy's orchestra, including trumpeter Charlie Shavers and tenor saxophonist Boomie Richman.)

June 1948 saw Elman start another band, which opened at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco that month and performed at the Hollywood Palladium later during the summer.

How often did Martin get to hear his father play live?

"A good percentage of my life," he reminisced. "When I was very young, I would go down to the ballrooms with my mom and dad. And then [ he'd ] do the shows, and then I would come home with him at night."

Elman worked with old friend Jo Stafford on her ABC radio program in the fall of 1948, and, about a year after that, subbed for arranger Axel Stordahl, leading an orchestra behind Frank Sinatra on the "Lucky Strike Light Up Time" radio show which originated in New York City.

He also cut a lot more records for MGM into 1952, including a whole series which included Samba with Zig, Rhumba with Zig, Zig's Polka, Zig's Mambo, and Marchin' with Zig, presumably done with studio musicians.

Similar to some other leaders, Elman gave up his big band once and for all, when the public's fancy turned away from good music.

"Yes, it affected him very much," Martin acknowledged. "He just thought it was a phase and would come back. At that point, big bands were becoming too expensive. You know, you've got 17 to 20-piece orchestras, and everybody else is working with . . .

little groups. There was just no room for them anymore."

During the 1950s, Elman worked mostly on television broadcasts from Hollywood, such as "The Dinah Shore Show."

"Oh yeah, he was doing shows almost every day," Martin recalled. "Back then, it was basically kinescopes - live tape. And I would drive him to the shows and drive him home a lot. He was so tired. He was working a lot of hours."

On the ride home, he would talk about typical father-son things, rather than, for instance, what he had just played.

"Just normal," Martin confirmed. "Just a normal family."

Elman also worked in the recording and movie studios, but even if no paying jobs were scheduled on any given day, he was still ready to go.

"Oh yeah, at home he practiced his horn," Martin reported. "And we'd be out doing things or driving somewhere and he would just have the mouthpiece, you know. Just tuning it. He had to keep his lips very strong."

Oddly, when "The Benny Goodman Story" movie was made, Elman appeared on-screen, but his trumpet part on the soundtrack was "ghosted" by Manny Klein.

"I didn't know anything about it until years later," Martin confessed. "I never knew he was doing it. Until I saw it on television . . . He was very quiet. He didn't talk much about anything (different things that he was doing). I didn't even know he was in some of the Mickey Rooney movies 'til years later when I saw 'em."

In July 1956, Elman suffered a serious heart attack. He never fully regained his strength, and was forced to take a job at a car dealership (!).

Tommy Dorsey died in November 1956, and while his estate was being settled over the next two years, one press item claimed Elman would take over the band.

"There was talk of it," Martin confirmed. "It never came about."

Elman was selected by Dorsey's former manager, Tino Barzie, to be a part of a touring show, "The Music of Tommy Dorsey Lives On," which was organized in 1961. It featured a new edition of TD's band, under Sam Donahue's direction, along with the Pied Pipers and Frank Sinatra Jr. But Elman was dropped from the tour.

Perhaps the biggest humiliation came around October 1961, when Elman's second spouse, Ruby, filed an alimony suit. A partial transcript was printed in Down Beat:

"Pleading strained financial straits, the trumpeter testified that six of his seven bank balances range between $1.19 and $11. The seventh, he confessed, is overdrawn.

Unmoved, his wife's attorney questioned Elman. 'You are known as the world's leading trumpeter?' asked the lawyer.

Replied Ziggy, 'Lots of people think I am, but I still can't get much work.'"

To partially fill the void, Elman offered trumpet lessons out of his home.

"Well, my dad tried to get me to play trumpet, but I wasn't interested," Martin reminisced. "I was too young."

One of Elman's students was Herb Alpert, who later had many record hits as leader of the Tijuana Brass.

"Yes, way, way back," Martin said. "I really didn't know that until I read it . . . In 1966 or '67, he [ Alpert ] did And the Angels Sing, put it on one of his albums."

That provided Elman some happiness.

"Sure it did," Martin affirmed.

Meanwhile, Elman had become

co-owner of a music store.

"He was in business with someone down in Santa Monica," Martin confirmed. "I can't remember the guy's name now."

Elman was re-united with Benny Goodman [ shown, l. ] one last time, at a dinner party in January 1968,

commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Carnegie Hall concert. Less than six months later, Elman passed away, at age 54.

"I was basically off on my own," Martin recalled. "I think I had probably moved out. You know, as a young kid, you just forget about your parents. You have your own life < chuckles >."

Nowadays, his son has entered the entertainment business.

"I work for a company... we do commercials and movies and music videos," Martin stated. "Most of my family was in show business. I finally got in there, somehow

< laughs >."

Should Elman's horn come on the radio today, even if it's in the background, he can usually pick it out.

"A very distinct sound, over and above the other trumpet players," Martin emphasized. "I can basically tell the difference . . . I like the way it sounds."

"Ziggy was an excellent trumpet player," Noni Bernardi, now 94, told me. "I enjoyed him very much."

Bernardi worked with several other name bands in the '40s, and went on to serve many years on the Los Angeles City Council, from 1961 to 1993.

"Well, it was an honor and a pleasure working in both," he exclaimed. "I can't complain about which one was the best. I enjoyed both!"

As late as April 12th, 2000, Bernardi [ r. ] conducted a 16-piece big band for swing dancing at the Sportsman's Lodge in Studio City, CA.

"I have a lot to be thankful for," he pointed out. "Being in the music business, being in the music field that I was in. I enjoyed it so much, and I had the honor of playing with so many excellent players."

After Elman died, he sponsored a City Council resolution celebrating Ziggy's career.