sources:

Gibson, Gwen. "Hampton tap-dances around old

age at 86," Canton [ OH ] Repository,

Nov. 25, 1994.

Hampton, Lionel with James Haskins. Hamp:

An Autobiography (New York City: Warner

Books, 1989).

International 2002 Who's Who in Popular Music,

p.216.

Mandel, Howard. "First-Person Project: Gate,"

DownBeat, Mar. 2000, p.36+.

Popa, Christopher. Interview with Phil Leshin,

Jan. 26, 2005.

Woodard, Josef. "Education Vibe: Lionel

Hampton," Jazz Education Guide 2000/2001,

pp.22-27.

LIONEL HAMPTON

"Music Was His Fountain of Youth"

by Christopher Popa December 2006

He was not the first jazz musician to take up the vibraphone, but he was the first to give the instrument an identity in jazz, applying a wide range of attacks and generating remarkable swing.

"Well, I had been an admirer of his since I was 11 years old," Phil Leshin, his manager, reminisced to me. "I didn't become his manager until late in his life. I was his publicist before that."

Though Hampton flirted with contemporary rhythms and influences, he basically catered to the public with a steady serving of bebop, rebop, boogie, and bounce for more than five decades. Undoubtedly, it was the joy of entertaining which kept him going so long.

"There were certain things about the past that Lionel liked," Leshin pointed out. "You know, Lionel was a drummer originally, and he loved shuffle rhythm. And the shuffle rhythm that he used in his band was like the beginning of rhythm and blues; a lot of people say it was like the beginning of rock and roll. And he'd make every drummer play that shuffle rhythm, and a lot of them did not like to do that, because bebop was in. They wanted to play differently, and looser. But they had to play it that way. And, in retrospect, I'd say Lionel was right, because it gave the band a pulse and an excitement that other bands did not have."

Phil Leshin, 2002

Leshin first met Hampton in-person sometime during the 1950s.

"Let me think now," he started. "I guess I first met him when I was a bass player with Buddy Rich, and the bands used to pass each other in towns, as we played in the same venues."

He didn't try to get a job with Hampton, just to express his appreciation of his music.

"No," Leshin said. "I was just a fan."

Yet once Leshin began to work for Hampton, it wasn't strictly business.

"No, I was very close to him personally," he explained. "I used to go to his house to pick him up, if we had to go to an interview or some particular

event. And I would arrive early, and I would sit down at his piano and start playing some song. And Lionel would come out and he'd sit down next to me, and he'd say, 'Now when you get to the bridge, you've got to use some different changes. Try these.' And he would show me different chord changes for the bridge of some standard song that I was playing."

On a few occasions, Leshin even appeared on-stage in Hampton's band, on acoustic bass.

"Yeah, a couple of times," Leshin recalled. "Oh, I loved it. I mean, first of all, I knew the music. I'd loved it and had been listening to it for years. And, one day at the Riverboat in New York, his bass player didn't show up and the show was about to begin. And I was in the audience, handing out press releases. And he said, 'Phil Leshin, come down here, play bass, 'cause "Skinny" Burgan's not here' (that was the name of the bass player). And so I went down and I played; I played most of the night with him."

vital stats:

given name Lionel Leo

Hampton

birth Apr. 20, 1908,

Louisville, KY

death Aug. 31, 2002,

heart failure, New York

City

father Charles Edward

Hampton, a railroad

worker, d.1940?

mother Gertrude Morgan

Hampton

grandfather Richard

Morgan, railroad

fireman, b.1861?

grandmother Louvenia Morgan, an

evangelist

wife Gladys Riddle, a former dressmaker,

m.Nov. 11, 1936, Yuma, AZ; d.1971,

heart attack

education Doolittle School, Chicago, IL;

Holy Rosary Academy, Collins, WI

interests baseball

honors and awards voted into the Playboy

all-star band 28 years in succession;

Ebony Lifetime Achievement Award,

1979; appointed UN Ambassador of

Music, 1985; numerous honorary MusD

and PhD Music from various colleges

and universities

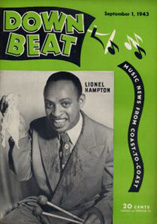

Lionel Hampton,

ca.1940

Once, some sources gave Hampton's birthdate as 1913 or 1914, rather than 1908.

"He got very vain at one point in his life," Leshin observed. "He says, 'Man, I can't be that old, change it.' He was trying to do that, but I told him, 'Lionel, you can't do that. Everybody knows when you were born.' In fact, there's a commemorative plaque hanging in Louisville, I believe in the Booker T. Washington Library, that says 'Lionel Hampton was born here in Louisville' and there's a copy of his birth certificate there."

Vanity aside, Hampton had a number of admirable qualities which Leshin noticed, such as being very devoted to and trusting of his wife, Gladys.

"Well, certainly, Gladys played a big role in his life," he said. "Lionel had no idea about money. He couldn't care... he knew he just liked to have a lot of it, but he couldn't hold onto it. If you gave him a thousand dollars in hundred-dollar bills, he'd go out on the street and he'd give it away, before he got home for dinner. So Gladys made sure that there was money left to take care of him, and them, until... well, she died a long time ago... but there was enough left to take care of Lionel 'til he died."

Gladys had made a lot of major business decisions on Hampton's behalf, running the company which had been named after the couple, Glad-Hamp.

"Oh, absolutely, she did," Leshin confirmed. "She's the one who actually hired me; it was Gladys who called me, to ask me to become his publicist."

Dealing with money on that high level, Leshin agreed that Gladys had to be the tough one of the two.

"Of course," he acknowledged. "Lionel never said a word."

When Hampton did talk, he expressed an enthusiasm for music and liked to reminisce about his life and experiences.

"Yeah, he talked about his days, from when he first started," Leshin said. "Lionel always spoke about two people who mostly influenced him in his life: one was Benny Goodman, and the other was Louis Armstrong. And he played with both of them."

Hampton was part of a great achievement, helping to break down the color barrier in 1936, as one member of The Benny Goodman Quartet.

"Oh, certainly. It was really Benny's achievement," Leshin corrected me.

As the famous story goes, Goodman first listened to Hampton at the Paradise Club, a tavern on Central Avenue in Los Angeles.

"John Hammond had heard about Lionel, and, at that time, Benny already had Teddy Wilson playing, with the Trio, with Gene Krupa," Leshin stated. "Lionel described it very funny. He said, 'I'm standing there on the bandstand and I'm playing, and all of a sudden I hear this clarinet that was beautiful! And I look up and there was Benny Goodman, he's sitting in with me. And then I see that the drummer changed, and Gene Krupa was playing the drums. And they got rid of my piano player and Teddy was playing piano. And we played on that bandstand for hours, and it was wonderful! And the next day I got a phone call from Benny, asking if I would like to join the band and play with the Quartet.' The Trio would become a Quartet within the band. And that's how that happened. And he said, 'Wherever we went, we were treated just the way the other members of the band were. Otherwise, Benny wouldn't take the job.'"

As for Armstrong, there was an equally well-known tale of Hampton at a recording session with him in 1930, getting invited by Armstrong to play the set of vibes which was over in the corner of the studio.

"He worshipped Louis when he was a young guy, coming up, and wound up getting a job as a chaffeur, at one point, just so he could get to meet him," Leshin noted.

In His Own Words, Lionel Hampton On Louis Armstrong

"Well, Louis was my idol. I met him, we were talking, then he said, 'Oh, I got to call a car so I can go to the city and go to work.' And I said, 'You don't need a car, you can use my car.' So I took him where he was going. yeah, we hit it off."

"Louis used to sing 'Rockin' Chair Got Me' and I'd be the old man in the rocking chair. 'Old rockin' chair's got you, father, cane by your side,' he'd sing to me, and I'd have on a duster coat, a false beard, an old straw hat and a cane-my props. Oh, boy! I thought I was something, doing that with Louis Armstrong!"

"Louis and I did an act on 'Hold That Tiger.' I'd go into the audience hollering through my snare drum: 'Oh! (Hold that tiger!), Oh! (Hold that tiger!).' And on the last one, when Louis hit that high C or F-which in those days, every trumpet player would try to hit, but Louis would hit it and hold it-I'd run from the audience and slide on my belly, with the snare drum on, across the dance floor, and hit the cymbal I'd set up with my bass drum on the floor. I'd hit my cymbal to cut off Louis' high note, and the band would cut off, too, and we never missed, we'd always hit it right on time. People got a big kick out of that. Yeah, Louis and I were tight."

Between 1937 and 1941, Hampton recorded with many other great jazz musicians, playing in an informal, jam session fashion, on Victor. (He was billed as leader, but the sidemen came from the other people's bands, including some from Benny Goodman's and Duke Ellington's.)

"When I was 11 years old, I heard those RCA records," Leshin recalled. "Yes, they were wonderful!"

recommended listening - select list

The Mood That I'm In Lionel Hampton, vocal Feb. 8, 1937, Victor

Whoa, Babe Lionel Hampton, vocal Apr. 14, 1937, Victor

The Object of My Affection Lionel Hampton, vocal

Sept. 5, 1937, Victor

Hot Mallets Sept. 11, 1939, Victor

Central Avenue Breakdown Lionel Hampton, piano

May 10, 1940, Victor

Flying Home May 26, 1942, Decca

Flying Home No.2 Mar. 2, 1944, Decca

Hamp's Boogie Woogie Milt Buckner, arr. Mar. 2, 1944, Decca

Beulah's Boogie Dardanelle Breckenbridge, arr. May 21, 1945,

Decca

Hey! Ba-Ba-Re-Bop Lionel Hampton and band, vocals

Dec. 1, 1945, Decca

Adam Blew His Hat Sept. 9, 1946, Decca

Hamp's Walkin' Boogie Sept. 17, 1946, Decca

Gone Again Winnie Brown, vocal Aug. 6, 1947, Decca

Three Minutes On 52nd Street Aug. 6, 1947, Decca

Midnight Sun Nov. 10, 1947, Decca

Rag Mop The Hamptones, vocal Dec. 29, 1949, Decca

Birmingham Bounce Roy Johnson and Freddy Hamilton, vocals

Apr. 21, 1950, Decca

September in the Rain Gil Bernal, vocal Jul. 25, 1950, Decca

Star Dust Jul. 22, 1954, Trianon Ballroom, Chicago

Speak Low Mar. 21, 1960, Columbia

Sweet Georgia Brown Lionel Hampton, vocal 1984 "Big Bands At Disneyland"

telecast

P.S. I Love You 1984 "Big Bands At Disneyland" telecast

Hampton formed his own big band in 1940, and the majority of his career was documented with recordings for Victor, Decca, MGM, Verve, Columbia, and other labels, including his own Glad-Hamp imprint.

"You have no idea how many records are out there," Leshin warned.

A good number have remained available in one format (78s, then LPs) or another (now CDs).

"Yeah, they are. I don't have to do anything, they just are," he remarked.

Yet, even for a long-established star like Hampton, record companies were seldom as forthcoming as they could be.

"No, don't be ridiculous!" Leshin barked. "Record companies notoriously manipulate funds and hold back money. And try to make sure if you have six records out, you'll get paid for four, you won't get paid for six. And that the amount that you get paid is usually not the amount that had been agreed upon. Record companies are like movie companies --- they are thieves!"

It can be daunting for an individual to take on a corporation, especially the international conglomerates that record companies have become nowadays.

"I couldn't take on a corporation, except to catch them and have a lawyer say, 'That's not what the contract called for,'" he explained.

The musicians in Hampton's bands read (at various times) like a jazz and r&b who's-who, including Marshall Royal, Cat Anderson, Earl Bostic, Arnett Cobb, Milt Buckner, Illinois Jacquet, Al Grey, Dinah Washington, and Quincy Jones.

In the early '90s, Hampton appeared and recorded with a group of all-stars dubbed "The Golden Men of Jazz."

"Those were all guys that Lionel had played with all of his life," Leshin noted.

They included "Sweets" Edison and Clark Terry on trumpets, Al Grey on trombone, Hank Jones at the piano, and Milt Hinton on bass.

"And that was a tough thing putting it together, because Lionel also had a colossal ego," according to Leshin. "He wanted all the applause to be for him, and he hated it when somebody else on-stage got applause. But that's very common with people in show business."

The same charge was often made against Benny Goodman.

"Benny Goodman definitely was the same way," Leshin commented.

Similar to the "Golden Men of Jazz," it potentially could have been difficult with the billing for reunions of the Goodman Quartet which started in the 1960s and '70s, since each of the sidemen had, by that time, become superstars.

"That's correct," Leshin answered. "Well, it was Lionel who got them together. I was there. We did a show at Macy's [ in New York City ]; it was financed by the department store. They wanted to push their record department, so Lionel convinced Benny, Gene, and Teddy to come up to the Music department at Macy's and we'd play with the Quartet. Nobody had to be the leader; it didn't matter. They all knew the songs. They knew each other. They knew how to play. All they had to do was say, 'Hey, let's play so-and-so.' Everybody would say, 'Okay.' It was no big deal."

But who do you give top billing to, when they all might want or deserve it?

"It definitely was a reunion of the Benny Goodman Quartet, featuring Lionel Hampton, Gene Krupa, and Teddy Wilson," Leshin dismissed.

Where did Hampton get his famous penchant for showy antics - including dancing, parading, and [ r. ] jumping?

"From watching Louis Armstrong," Leshin suggested. "I would think that's probably it. And, also, in the early days of the music business, the black musicians grew up alongside of the vaudeville people. You know, like [ dancer ] Stumpin' Stumpy and [ comedian ] Redd Foxx and all of those people. I mean, when we played the Apollo Theatre... and I played it many times with Buddy Rich, and many times with Lionel Hampton... Lionel actually holds the record at the Apollo Theatre... there used to be lines four abreast going all the way around that huge block, from 8th Avenue to 7th Avenue, waiting to get in for the next show. And as soon as we got off the stand -- we'd be outside with a glass of water or something -- and it was almost time to go back and play the next show."

To achieve and maintain such an energetic stage presence, would Hampton exercise?

"No, just by playing," Leshin responded. "I mean, he used to come down and would jump up on one drum that was set up on the stage. When he did Flying Home, at the end of it, he'd jump up on the drum, physically."

In His Own Words, Lionel Hampton On Himself

"Music is my fountain of youth. It keeps me contemporary . . . "

" . . . I had my push on jazz when I was a kid and lived in Chicago. My family had moved there from Alabama. My uncle Richard Morgan used to take me around to the night clubs where musicians from New Orleans were playing. And I got a dose of that music . . ."

". . . I always treated vibes as a serious instrument, not a novelty . . . You hear when I play some of my passages that my riffs have a classical background. That came naturally because I listened to all types of music. I tended to think a lot of good music was classical music. But you had to know where to put it at."

"So many youngsters growing up now can play good, but they have a little something missing. Maybe it's ideas, or execution. They might be missing something . . . "

In the 1960s and '70s, Hampton was truly a world-famous musician, but he had Leshin working on his behalf, spreading publicity.

"And that I've done for -- my God -- 30, 40 years," Leshin observed. "And that was just to make sure wherever he played, people knew he was coming to town. And any new records he was putting out, I

promoted him, in effect."

"Yeah, it's partially reinforcement," he continued. "In the publicity business, you're only as famous < chuckles > as your last story in the newspaper, or on television. So, you have to keep going. You do have to keep reinforcing it, but you also have to say what's new and different, so when there are changes made in the band, when there's a new arranger, new soloists added, that the public knows about that."

Phil Leshin plays the piano [ l. ]

while he and other friends wish Hampton a happy 93rd birthday, 2001

There's an old adage which states, to the effect of, "All publicity is good publicity, as long as they spell your name right." Does Leshin subscribe to that?

"Sometimes I do. Yeah, it's often the case," he reasoned. "The public seems to have a very short memory."

However, they seem to want negative things.

"They want negative things," Leshin allowed. "But the thing they remember from the story is your name."

In 1989, Leshin succeeded Bill Titone as Hampton's manager.

"Lionel and his lawyer called me, and asked me to take over, 'cause Bill was going to be leaving," Leshin reported. "But my duties after I became his manager were to take over the financial dealings of the company. And that meant making sure he got his royalties paid from all the records he's made over the years, and to help to negotiate contracts for the band."

Hampton continued to lead a big band into the 1990s, even when economics challenged its existence.

"He wanted a big band," Leshin confided. "He was like Buddy Rich [ pictured l., alongside Hampton ] with that. When I was with Buddy, we'd get calls from an agent who -- I'm going 'way back -- and he'd say, 'Look, we've got $5,000 for the band. You can either get a quintet or 16 pieces, it's up to you, but all we got is $5,000. Buddy would always go for 15 or 16 pieces. Lionel was the same way. He wanted to hear a big brass section, a big sax section, and a full rhythm section. The money went for the name of 'Lionel Hampton.'"

Throughout the years, Hampton received many awards and honors, but didn't seem to favor one over another.

"No, he liked them all," Leshin asserted. "He loved getting honored. He loved getting all those honorary doctorates -- God, he had about sixteen or seventeen of them, by the time he died."

In 1971, Hampton began a couple of philanthropic initiatives, the Lionel Hampton Project Houses and the Gladys Hampton Project Houses, offering affordable housing to low-income families.

"The Gladys Hampton Houses are in Newark, the Lionel Hampton Houses in Harlem," Leshin stated. "I got to tell you, I ran into a mailman one day, who told me he delivered mail in all the houses in that part of Harlem, and the best run was the Lionel Hampton Houses. He said it was always clean and orderly, the elevators worked, the garbage was taken out, all those kinds of things."

For many years, Hampton was quite active on behalf of the Republican political party. In fact, he had been the first African-American to perform at a presidential inaugural, when he played at Harry Truman's gala on January 19, 1949 at the Armory in Washington, D.C..

"Absolutely," Leshin confirmed. "Well, he inherited Republicanism from his grandparents. Don't forget that Lionel was only a generation removed from slavery. I mean, he died in his 90s. And his parents had been slaves for at least part of their lives, and so they loved Abraham Lincoln. And when they got the right to vote, they became Republicans because of Lincoln. And he stuck with the Republican party."

So, on a regular basis, Hampton helped to campaign for the national Republican candidate for President, as well as for local or state candidates he believed in.

"Oh, yes, politically, he was very conservative," Leshin said.

There was one exception: Hampton supported Clinton-Gore in 1996.

"He did. That was probably my doing," Leshin admitted. "Well, we were watching the Republican convention on television together. And Pat Robertson got up and made a speech, and Jerry Falwell made a speech, and then Pat Buchanan made a speech. And I said, 'Lionel, how can you go along with a party that has these people speaking for it, and adding their positions to the platform?' And then I would convince him that Bill Clinton was a much better candidate and would have been a better President. So I set up a meeting between him and Bill Clinton at the... I'm trying to remember the name of the hotel... Clinton was coming in to give a speech somewhere, to New York City, and we had a photo opportunity there at the hotel. (It was around the corner from the Waldorf, on Lexington Avenue.) And that picture wound up on the front page of The New York Times, with Lionel standing next to Bill Clinton, and Congressman Rangel standing next to him. And above that was a photograph of Bob Dole, whom, incidentally, Lionel liked, but he said, 'He's being crushed by these other guys in the party.'"

Getting back to the subject of Hampton proper, what words would Leshin the publicist use to describe him?

"He was gentle, he was sweet, he was kind," Leshin answered. "There was a buoyancy and a joy in his playing, as well as phenomenal technique and musicality . . . And he was covered with perspiration when he finished. Incidentally, so was Buddy Rich. They were the two guys I know who sweated -- constantly -- when they performed."

Hampton had a reputation for driving audiences to near-hysterical excitement.

"He used to be able to get up on the vibes and play for hours. You'd have to pull him off stand!," Leshin continued. "A lot of theater owners and club owners complained about it, 'cause they wanted to turn over the room and get in another group of people. But it was impossible to get him off the stand. If he felt he was hot and was playing good and the band was playing good, he wanted more, more, more!"

But Hampton's health began to decline in the 1980s, and took a real nosedive during the '90s.

"He had lost his power and his strength -- he'd had a series of strokes, and, of course, couldn't move the way he did," Leshin recalled. "He had terrible problems with his eyes - cataracts and glaucoma. So, you know, that was pretty serious, for a guy who was as active as he was."

Surprisingly, Hampton still wanted to continue performing, so Leshin and others did the best they could to accomodate him.

"Music was his reason for being," Leshin observed. "We had a staff... we had a housekeeper, a nurse... we had a guy named Reuben, who was very good, who was his personal valet and got him dressed and shaved and made sure his clothes were in order. And another guy named Bill Bergacs, who was in charge of the instruments and the musicians. Actually, he would be the band manager, and he would make sure that the stands were up and the sound was right."

Near the end, there was a problem involving Hampton and taxes not being filed or paid to the government, eerily similar to what became a relentless tax burden for Woody Herman.

"I pretty much worked out the deal with the I.R.S., to please wait until after he died, 'cause we needed whatever money was there," Leshin said. "Woody got royally screwed. That was horrible . . . what they did to him."

Did Hampton ever talk of retirement?

"Never, never," Leshin assured me. "The last minute, when he was dying in his hospital bed, he said, 'See if you can set up a tour for Europe.'"

send feedback about Lionel Hampton: "Music Was His Fountain of Youth" via e-mail

return to "Biographical Sketches" directory

go to Big Band Library homepage

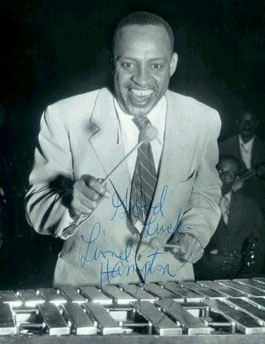

A 1942 theater appearance by Hampton

Weakened but still upbeat, 1990s.

Photo © Associated Press.