JACK TEAGARDEN

"Jazz Trombone Pioneer"

by Christopher Popa February 2006

Most critics and scholars have stated that he was the best on his horn, including Joe Showler, author of a new biography about him.

"Yeah, he certainly was the greatest trombone player ever," Showler observed. "He was as much an influence on the trombone as a jazz instrument as Armstrong was with the trumpet. They were both very influencing pioneers, as far as I'm concerned. I mean, everybody in the world wanted to play like Louis. Everybody who wanted to play trombone wanted to play it like Jack."

inspires you to reach a little further and a little deeper to, you know, to do a better job yourself."

Teagarden decided to form his own small group in 1951, which toured Britain and Europe in 1957, as well as the Middle and Far East in 1958-59. He reunited with his mother, sister, and Charlie for a performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival in September 1963. But he had started drinking again the year before, and wasn't in good health.

"Certainly at the end, everything was wrong," Showler confirmed. "His heart was enlarged, his liver was shot, every organ in his body was screwed up. He was just real, real sick. He shouldn't have even been outside. He should have been in a hospital bed."

A few months later, Teagarden was found by a maid, in his hotel room, dead of pneumonia.

"He got pneumonia back in the mid-'30s, and so he was prone to getting to pneumonia. And he got it several times over the years," Showler noted.

I asked him about the beautiful words that are written on Teagarden's gravestone: "Where there is hatred, let me sow love."

"Addie just picked that out of a book," Showler revealed. "It comes from the prayers of St. Francis of Assisi."

But, rather than the marker, it is Teagarden's recordings that have served as his best memorial.

"I guess some of the classic records he left us over the years," Showler agreed. "That wonderful quality of sound, nobody else could ever get that sound."

Once Showler's biography comes out, I'm sure that it will further remind everyone of Teagarden's legacy.

vital stats

given name: Weldon Leo "Jack" / "Big T"

Teagarden

birth: Aug. 20, 1905, Vernon, TX

death: Jan. 15, 1964, New Orleans, LA,

bronchial pneumonia

father: Charles Teagarden, b. 1878, d.

Nov. 4, 1918, worked on cotton oil gins

and was a part-time cornetist

mother: Helen Giengar Teagarden, b.

Jan. 31, 1890, d. 1982, a piano

instructor and theater pianist

sister: Norma Louise Teagarden

Friedlander, b. Apr. 28, 1911, d.

June 6, 1996, a pianist

brother: Charles Eugene "Charlie" /

"Little T" Teagarden, b.Jul. 19, 1913, d.

Dec. 10, 1984, a trumpeter

brother: Clois Lee "Cub" Teagarden,

b. Dec. 16, 1915, d. 1969, a drummer

education: public schools, Vernon, TX

wife: Ora Binyon, m. 1924, div. 1932

sons: Gilbert; Jack Jr.

wife: Clare Manzi, m. 1932, div. 1936

wife: Edna Lillian "Billie" Coates,

m. Mar. 25, 1936, div. 1942

wife: Adeline "Addie" Barriere Gault,

m. Sept. 1942, d. Feb. 1997

children: Vernajean Atwell[ foster

daughter ]; Joseph "Joe", b.1952

residence: 3253 Tareco Dr., Los Angeles,

CA ('50s); Pompano Beach, FL (1961-)

Showler has celebrated Teagarden's music for more than four decades.

"I've spent my entire life researching Jack Teagarden, and the Jack Teagarden family," he acknowledged.

He has, for instance, made for television an award-winning 2-hour documentary about Teagarden's career, written articles and liner notes, provided recordings, and loaned photographs, all so that others can share in his enjoyment.

But Showler's crowning achievement, written during the last three or so years, is his story of Teagarden's life and career. It has 28 chapters and is 1,000 pages long.

"I need three months to do some rewriting, polishing, photo selection and indexing (which is like writing another book)," he informed me.

Did he ever get to meet Teagarden?

"No, I met everybody else," he said. "I met his mother, and I met Charlie, and I met Norma, and a lot of other relatives."

Showler's book should, once and for all, correct some long-standing errors, such as Teagarden's given name and the date of his birth, that have appeared elsewhere.

I noticed just two months ago that no less than the United Press International (UPI) claimed that Teagarden was born December 19 [ way wrong ] in 1895 [ also wrong ]!

It was his mother who encouraged Teagarden's interest in music, as he picked up the baritone horn at age 7 and the trombone soon after. He taught himself to play.

"That's one of the things that Charlie Teagarden used to say to me," Showler noted. "He said one of the reasons that Jack was so great is he didn't have anybody, any model, to pattern himself after . . . nowhere in Texas, I mean, he just wasn't influenced by anything."

Jack Teagarden... In His Own Words

"I never did believe in looking back . . . like we got to copy this record or this style note for note. I try to play better tomorrow than I do today. It's the only way I could ever see it."

"I'm bending over backwards these days trying to please the people with my kind of music, but I don't know if I'm reaching them. It's frustrating trying to fit yourself into this new world of music. You feel so insecure in what you're playing."

"Just want to go on playing as long as I'm able. I don't want to show off or outplay anybody. Just want to stay in the race-and to keep on plugging."

By the early '30s, Teagarden's trombone was in high regard.

"Well, I don't know that I've ever tried to analyze or put into words to try and describe his playing," Showler said to me. "Certainly, the blues-y quality is important . . . Probably the most obvious things that attracted me to his playing were hearing things that one doesn't expect to hear. I think, you know, in the improvisation, there are sometimes notes that certain great jazz players will play that are totally unexpected. You can always whistle a tune to yourself,

but you never really hear these guys play what you think is going to be obvious. And I just know that there's been a couple of times when Teagarden would just play one note and that would be so out of the left field, and, it was like, that would say more than anything, than any other individual soloist could say. I think the same thing with Louis. Louis could play something that would be a total surprise and it would just, kind of, really [ move ] you, because it works and it's not something you expect."

"One of the other qualities about his trombone, as far as I'm concerned, is his trombone didn't sound like a trombone," Showler went on. "Most trombone players sound very drone-y, a very drone-y sound. He had a nice, high-pitched sound to the instrument and played it more like a trumpet than a trombone. And he didn't do a lot of sliding into notes. He would hit them. And he used to say that the trombone players that he heard . . . in the days when he was starting, he said they seem to slide into the note, as if they were searching for it. He said he didn't like that style and that technique. He liked to just go right to the note and play it. So he had a different style and of playing, and he certainly had a different sound."

recommended listening - select list

Junk Man Casper Reardon, harp Brunswick, 1934

I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues Jack Teagarden, vocal

Brunswick, 1939

Especially for You Linda Keene, vocal Brunswick, 1939

I'm Takin' My Time with You Kitty Kallen, vocal Brunswick, 1939

I Found a New Baby Jack Teagarden, vocal broadcast, Sept. 27, 1939

Muddy River Blues Jack Teagarden, vocal Columbia, 1939

Beale Street Blues Jack Teagarden, vocal broadcast, Jan. 23, 1940

The Blues Varsity, 1940

"Norma once said that Jack could not play as loud as Charlie, and Jack would often have a struggle to keep up with Charlie, because Charlie was so forceful and such a strong player. Jack just couldn't keep up with him, when the two of them were on the bandstand together," Showler added. "I don't think Jack's not being a real loud player ever was a problem. And most of those guys played into microphones, anyway."

Any other clue to know it's Teagarden playing?

"Quite often, trombonists could play the triplets and some of the stylistic things that Jack could play, but you'd know it wasn't Teagarden, simply because the tone wasn't right. Nobody ever got that tone right," Showler answered.

Of course, Teagarden's distinctive singing will give it away, too.

"Well, his first wife said that he never sang a note, not even in the shower, when she was with him. And that all happened after he got to New York," Showler reported. "So, even though it has been suggested in a couple of books that he was singing as early as 1924, that does not seem to be the case. He didn't sing until he got to New York. In late '27 is when he got there, and I don't think he sang anything on records until about 1928."

Devil May Care Marianne Dunne, vocal Varsity, 1940

Accident'ly On Purpose Lynne Clark, vocal Viking, 1941

Dark Eyes Decca, 1941

Yankee Doodle Jack Teagarden, vocal Standard, 1941

Blue River Jack Teagarden, vocal Decca, 1941

Impressions of Meade Lux Lewis Standard, 1941

Stars Fell On Alabama as "Jack Teagarden's Chicagoans"

Jack Teagarden, vocal Capitol, 1943

If I Could Be with You (One Hour Tonight)

Jack Teagarden, vocal V-Disc, 1944

Basin Street Blues Jack Teagarden, vocal Standard, 1944

Aunt Hagar's Blues Jack Teagarden, vocal Standard, 1944

On the Road to Mandalay Teagarden Presents, 1946

A Monday Date Jack Teagarden, vocal Capitol, 1956

Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen Jack Teagarden, vocal

Capitol, 1956

From 1928 through early 1933, Teagarden was a member of drummer Ben Pollack's band.

"Well, the old tried-and-true story was that Pollack's girlfriend, Doris Robbins, who he met in '31, she kind of joined the band and Pollack fell so deeply in love with her that he . . . made his whole world surround her, and she became more and more featured with the band," Showler explained. "In fact, [ she ] even started making suggestions to Pollack about how he should manage and handle the band. So the band became, kind of, diverted from being a swinging jazz band to, more or less, a show band that featured her, and her ballads, and her own particular songs that she was good at. I think the guys just got . . . disillusioned with not being able to play the kind of music that they'd been used to playing. So when there was an opportunity to go somewhere else and play some real jazz, they decided to do it."

By the time Teagarden decided to leave Pollack, many of the other good soloists who had been with the band, including Jimmy McPartland and Benny Goodman, had already quit, too.

"Although they had left much, much earlier. They both left in, like, late '29, so Jack was still in the band through '30, '31, and '32, so losing those two soloists couldn't have had much of an impact on his decision to leave," Showler noted. "I think it was just the fact that the band was being . . . designed around Doris Robbins. And Sterling Bose was in the band, and he was, kind of, the catalyst for suggesting to Jack that they get out of the band."

Teagarden then joined the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, and stayed there until 1939. I was surprised when I read once that there might have been some element of boredom in that job, that supposedly Teagarden, while working with Whiteman's orchestra at the Drake Hotel in Chicago, said that he had just had a good night's sleep on the bandstand.

"Yeah, right, he told that to George Hoefer," Showler confirmed. "I don't think he cared whether he was being featured with Whiteman or not. He was getting paid well. He had security, and that's what he wanted . . . He wasn't

thinking about being number one in the spotlight, as a great jazz soloist or instrumentalist, or how he would go down in history. He just had a really damn good job . . . Charlie Teagarden once told me that during the Depression, they didn't know there was a Depression going on. They were traveling on the 'red carpet' all the way. And so, here's Jack having a nice rest of the bandstand and making $350 or $400 a week for doing nothing."

If he chose to, Teagarden could have some fun after work.

"He could jam all night with anybody he wanted to," Showler asserted.

When Teagarden started blowing trombone, in 1913, there were no real jazz players or jazz recordings for him to hear.

"I guess by the time Jack was proficient on the trombone, in 1920, some of the jazz musicians would have been listening to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and maybe a couple of other bands that started to record in 1917 and 1918," Showler said.

In 1921, Teagarden joined pianist Peck Kelley's band, in Houston, TX, and while he was there, he co-wrote I'm Gonna Stomp Mr. Henry Lee.

"He and Peck Kelley worked that tune out together," Showler said. "It was originally called Stomp It Mr. Kelly. And then when Jack got to New York, they called it I'm Gonna Stomp Mr. Henry Lee, and it was the same tune, and I've never been able to figure out who Henry Lee is. But anyway, I think Jack got a composer credit on the original recording that he did with Eddie Condon, and I think Condon's name went on it, as well. And then King Oliver did it about three weeks later, and called it My Good Man Sam."

Teagarden also received the credit, along with Glenn Miller, for coming up with the verse to Basin Street Blues.

"I don't know if Jack thought up any of these words, or if Glenn Miller thought up any of those words. And I don't think it's ever been stated anywhere, by either one of those guys, who did what. Like, whoever thought up 'Won't you come along with me...', I don't think we're ever going to know that," Showler reported. "I do know that Jack Teagarden told the story incorrectly for his entire life. He told the story that Red Nichols was going

to have a recording session, and they were going to do Basin Street Blues. And so Glenn Miller and Jack got together and started writing this new arrangement. Well, where Jack had got confused was that he had recorded Basin Street Blues with Red Nichols in June of '29, but they did the Spencer Williams arrangement at that time. And, although he did sing on it, there was no lyric. It was just, kind of, a . . . scat ad-lib vocal. You know, he didn't sing any words... he just 'da-da da-da,' this scat thing. And so, when they decided to record it under the direction of Benny Goodman, in 1931, in February I believe it was, the record eventually came out under the name of 'The Charleston Chasers.' And that's when that arrangement was written."

During his investigation, there was at least one thing Showler came across about Teagarden which especially surprised him, and will be in his book.

"He actually had to think twice about whether or not to go on his own, or stay with Whiteman," Showler confided. "And I thought that was so insane, because the five years he was with Whiteman, he was hardly ever featured or hardly ever heard. But yet, the security and the money were so great, it almost swayed him into staying and signing up for another five years. Thank God he didn't do it."

After working 4 years with Pollack and 5 years with Whiteman, was it a natural progression that Teagarden then formed his own band?

"Uh, no, I don't think so," Showler commented. "He wasn't a very disciplined man. He didn't have any business sense, and he was too much of a 'party guy,' and he was too much of a heavy drinker to be the leader of a big band."

But sidemen elevated to having their own bands was the mode of the day.

"I think because a lot of his contemporaries were going out and starting to lead their own bands, he kind of got trapped into thinking that was the thing to do," Showler reasoned. "I guess the big band era really started in '35, the swing era, and it seemed popular, if you were an outstanding soloist, to become a leader. When Benny Goodman did it, and then Tommy Dorsey did it, Berigan and all the rest of the star instrumentalists did it, then, I guess, they felt that Jack should do it, as well."

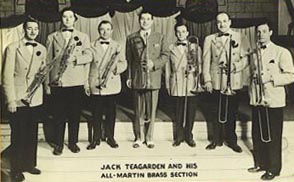

In 1939, Conn Musical Instruments asked Teagarden to endorse their trombone [ r. ]. The following year, Martin provided instruments for his trumpeters and trombonists [ below ].

Shown were [ l. to r. ] Tom Gonsalin, Sid Feller, John Fallstitch, Teagarden, Seymour Goldfinger, Jose Gutierrez, and Joe Ferrell.

Between 1939 and 1946, he led his own big band but it was not successful, and Showler blames Teagarden himself. "He was totally unreliable... would sometimes not show up. The band would have to work without him," Showler charged. "He was out partying, or doing some heavy drinking, or out with a gal, or doing something. He just was not a good businessman, and I think a lot of the promoters and radio people quickly realized that it was going to be difficult to deal with this band because of his unreliability . . . The other lack of success would be attributed to Jack's inability to communicate. He was not a good self-promoter. He was very much moody, shy, and introverted. The successful people... I think you can see, by their own personalities... outgoing and hard-driving people, and that would be Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw and Tommy Dorsey and, I don't know much about Harry James, I don't know about his personality, but I think you get the point of what I'm trying to say. A lot of it has got to do with 'the gift of the gab' . . . That's the same with anything in life, as well."

Ironically, Teagarden with his big band was probably playing better than he ever did.

"It was the one thing he was very passionate about. He loved that big band, and I can tell for the first couple of years, he worked pretty hard," Showler explained. "I can just tell by the effort he put into his solos and his playing. He was quite proud of it, and I can tell when he's feeling lazy and when he's not."

However, virtuosic talents don't necessarily guarantee success.

"I don't think so," Showler agreed. "I guess if you consider some of the other bandleaders had top-selling records . . . I guess Jimmy Dorsey's Green Eyes was a big seller for him. I guess most of the bands had one big record . . . I guess Jack didn't have anything like that."

In reissuing some of Teagarden's work since then, record company producers seemed to concentrate on the same, small group of performances, like, for instance, Swingin On the Teagarden Gate.

"I don't know that you can use reissuing as a guide to what was good then," Showler cautioned.

With the advent of CDs, a couple labels have reissued everything Teagarden made.

"I never understood why he did a lot of the stuff he did. Obviously, he wasn't making his own choices as to what was going to be recorded," Showler commented. "There's a lot of stuff on those Standard Transcriptions that I just don't even understand, unless some of it was because he was recording during the ASCAP ban and they were just doing BMI tunes . . . The major effect it had on Jack was his theme song, I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues, was ASCAP. He found a tune... it was his first trumpet player, Sid Feller, who did a lot of the arrangements... Sid Feller arranged for Jack (now where Jack got the tune, I'm not sure), but it was a tune called It's Time for 'T'. They actually recorded that tune for Standard Transcriptions. I have a few radio broadcasts from around 1940 where they actually used that theme on the radio. And so that was about the only major effect that the strike had on Teagarden, and, actually, I preferred It's Time for 'T' as a theme to I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues. I thought it was a better tune. I wish he had kept it."

Both the commercial recordings and the transcriptions for radio reflect Teagarden's fondness of featuring girl singers with his band, including Linda Keene, Kitty Kallen, and Dolores ("Dodie") O'Neill.

"Well, I think girls were a requirement. I don't think it had anything to do with whether he was fond of them or not," Showler countered. "I know he liked Kitty Kallen, he liked her the best. Oddly enough, the three vocalists you named were early in his big band days, and they were some of the best. But he had some of the worst vocalists. He really did. Some of his vocalists from the wartime... they were just awful, and they left us enough recordings to prove it as well."

During research for his book, Showler contacted some of Teagarden's former vocalists.

"I never had a lot of success at finding all of them, but I found a few of them," he stated. "I actually found one, and then lost her again. Somebody said that they'd found one of the girls in Las Vegas, and when I tried to telephone her, she had an unlisted telephone number, and I couldn't get anybody to hand-deliver a note to her . . . I just felt so terrible because she, kind of, slipped right away from me and I just couldn't contact her. But I guess I talked to, probably, four or five others."

"I think the band actually lasted until October of '46. Didn't everybody break up at that time?," Showler remarked. "I mean, the War was over. I think after the War the big bands... they all started to come apart. I think it had something to do with the economy. It was just too expensive to carry that many guys on the road. I know that MCA was having some trouble getting Jack bookings. They couldn't get the price that they needed to carry that much personnel. I've got a long, long telegram... in fact, it's two telegrams... from MCA saying to Jack that they really wanted him to get off the road, because the band wasn't paying for itself anymore. In fact, one of the last big engagements, Jack was scheduled to go back into the Sherman in Chicago... and I've got the original contract here... and that got cancelled because the band folded up."

It was reported that Teagarden had to file for bankruptcy.

"One of the guys on the band, Clint Garvin, said that Jack Teagarden was paying his sidemen more money than any other bandleader was. I think Clint said they were making $65 a week and the other major bands were paying fifty a week. He may have had a top-heavy payroll. That is the only thing that I can think of that would have forced him into bankruptcy... that payroll was costing more than the band was bringing in," Showler observed. "But then, Jack was not setting the prices, nor was he setting up the individual engagements. I mean, that was all done by a management office, and I don't know why his management office was allowing him to carry such a heavy payroll when they knew how much the band was going to make for a ballroom or a one-nighter."

Venues from Teagarden's 1942-45 itineraries included typical stops like the Trianon Ballroom in Southgate, CA and the Pacific Square Ballroom in San Diego, CA, along with wartime appearances at Sheppard Field in Witchita Falls, TX; Bartsdale Field in Shreveport, LA; Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, NC; and Camp Crowder in Joplin, MO.

"Jack wanted to keep the band," Showler explained. "His wife, Addie, said that he was terribly upset and depressed when he lost that big band, 'cause he loved it so much. It caused a lot of problems between the two of them. In fact, they split up after the band folded. He was really disappointed about having to let that big band go."

Teagarden himself supposedly remarked, "All I had left was an equity in the band bus . . . and the manager ran off to Mexico with the bus."

sources:

DeMichael, Don. "Jack Teagarden, 1905-1964: Impressions of Big T,"

DownBeat, Feb. 27, 1964, pp.11-12.

Dupuis, Robert. "Jack Teagarden: Trombonist, singer," in

Contemporary Musicians: Volume 10, (Detroit: Gale Research,

Inc., 199?), pp.246-250.

Feather, Leonard. The Encyclopedia of Jazz (New York City:

Horizon Press, 1960), pp.438-439.

---. The Encyclopedia of Jazz in the Sixties (New York City:

Horizon Press, Inc., 1966), p.272.

Showler, Joe. E-mails to author, Feb. 21 and 22, 2006.

---. Interview with author, Feb. 11, 2005.

---. "Weldon Leo Teagarden: August 20, 1905 - January 15, 1964,"

Joslin's Jazz Journal, Nov. 2005, pp.10-11.

Start, Clarissa. "Mr. Tea Goes Home," Milwaukee Journal,

Sept. 7, 1941.

Tynan, John. "Teagarden Talks," DownBeat, Mar. 1957.

United Press International. "News Track: The Almanac," upi.com,

Dec. 19, 2005.

Waters, Howard J. Jr. Jack Teagarden's Music: His Career and

Recordings (Stanhope, NJ: Walter C. Allen, 1960).

Who's Who in America: Volume 32 (1962-1963) (Chicago:

Marquis Who's Who, 1962), p.3099.

In 1947, Teagarden joined Louis Armstrong's small group and became one of Satchmo's featured "All-Stars."

"Well, I think, Jack Teagarden used to say that he would be inspired by working with somebody else who was good," Showler observed. "If he was working in good company, he would then be good himself. If he wasn't in good company, then he wasn't good himself. And I think he needed the inspiration, and I think that it's the same with anything in life. If you're working with somebody who's exceptionally good at something, it, in turn,