When Auld organized his own big band, he continued to play with gusto and explored new sounds in jazz.

Critic-author Leonard Feather referred to Auld's 1943 ensemble as "a manic bunch of youthful beboppers."

They appeared across the country, including an engagement which started on February 3, 1944 at the Commodore Hotel in New York City.

Reportedly due to "agency problems," Auld's band broke up the following December.

Over the next few years, he tried again a couple times, organizing a new band which performed for dancers at, for example, Eastwood Gardens in Denver, Colorado and Meyers Lake Park in Canton, Ohio in the fall of 1945.

Metronome even declared Auld's as the "band of the year," but not long afterwards declining business conditions forced him to instead lead smaller combos.

vital stats:

given name John Altwerger

birth May 19, 1919, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

death Jan. 8, 1990, Palm Springs, CA, lung cancer

mother's maiden name Ruza

brother Barney

brother

sister

wife Diane

military service U.S. Army, autumn 1942 to summer 1943

residence 1900 Quentin Rd., Brooklyn, NY (1951)

During 1944-46, Auld made records for the Apollo, Guild, and Musicraft labels, sometimes using his big road band and other times using small pickup groups with, among others, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and pianist Erroll Garner contributing solos.

Other musicians who were on those discs included, at various times, Sonny Berman, Charlie Shavers, Howard McGhee, Billy Butterfield, Al Killian, and Al Porcino (trumpets); Trummy Young, John D'Agostino, and George Arus (trombones); Musky Ruffo, Al Cohn, Manny Albam, and Serge Chaloff (saxophones); Morris Rayman or Israel Crosby or Chubby Jackson or Doc Goldberg (bass), Mike Bryan or Turk Van Lake (guitar); and Lou Fromm or Specs Powell or Shadow Wilson or Irv Kluger (drums).

Auld's biggest commercial success on records was, arguably, a series of ballads he played on the Coral label during 1951-55, such as Manhattan and Misty, accompanied by a large studio orchestra and group of voices.

He led a big band of all-stars on two LPs recorded in hi-fidelity for EmArcy in 1955 and 1956. Besides other familiar melodies, the albums offered new arrangements of Frankie and Johnny and Prisoner's Song, a pair of tunes which Auld had once played with Berigan.

Auld also gained notoriety from a couple of supportive acting roles.

In "The Rat Race," a 1949 Broadway play about a musician and a dance hall hostess, he portrayed a saxophonist. ("The Rat Race" was later made into a movie, featuring Tony Curtis and Debbie Reynolds.)

In 1971, Auld worked for Garson Kanin in "Idiot's Delight" with Jack Lemmon at the Ahmanson in Los Angeles.

For the 1977 motion picture release "New York, New York," which starred Robert DeNiro and Liza Minnelli, Auld taught DeNiro how to hold the saxophone and depress its keys. He also appeared in the film himself as a (fictitious) bandleader named "Frankie Harte" and was the principal soloist on the movie's soundtrack.

Though he enjoyed acting, music remained Auld's primary focus.

He owned and operated his own club, the "Georgie Auld on Times Square" bar in New York City, worked on the staff at MGM studios in Hollywood, and - as did a number of instrumentalists of his generation - began performing overseas. He went to Japan eight times during the late 1950s and early '60s, and to Europe in 1962.

However, in the U.S., employment from the '60s on proved somewhat spotty.

He took a variety of jobs in Las Vegas, served as conductor for vocalist Tony Martin in 1967 (touring Europe and South America), and was a sideman in the band on comedian Flip Wilson's TV show.

He continued to visit Japan, where, by 1975, he had recorded some 15 albums, many of them quite well-received.

Auld's final American recordings, besides the soundtrack work for "New York, New York," included Don't Explain, heard in "Lady Sings the Blues," a 1972 film biography which cast pop singer Diana Ross as jazz legend Billie Holiday, and Song of India / Disco Boogie, a 12" single done in 1976 (D&M Sound 124505).

During the 1980s, Auld occasionally performed around Los Angeles with a quartet.

I spoke with him briefly on the telephone, and tentatively set up an interview - but it didn't happen. Perhaps he preferred to continue working on his autobiography, titled Where Do I Go From Here?. With such a variety of experiences, the book likely would have been an interesting read, but it evidently was never published.

sources:

Ancestry.com, "California Death Index, 1940-1997."

"Auld, Georgie," in Who Is Who in Music (Chicago: Who Is Who in Music, Ltd., 1951).

Leonard Feather, "Auld, Georgie," in The Encyclopedia of Jazz (New York City: Horizon

Press, 1955), p.106.

---, "Auld, Georgie," in The Encyclopedia of Jazz in the Seventies (New York City:

Horizon Press, 1976), p.56.

---, "Jazz: Auld Times Revisited in Big Band Movie," Los Angeles Times, Sept. 5, 1976,

p.J78.

Burt A. Folkart, "Georgie Auld, 70; Self-Taught Saxophonist," Los Angeles Times, Jan.

11, 1990, p.26.

Charles Garrod and Bill Korst, Georgie Auld and His Orchestra (Zephyrhills, FL: Joyce

Record Club, 1992).

Jack Mirtle, The Music of Billy May: A Discography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

1998), pp.370-373.

Tony Shoppee, liner notes, "Georgie Auld and His Orchestra: 'jump, Georgie, jump'"

Hep ( UK ) CD 27, 1996.

I would like to expand this tribute with, if possible, a new interview of someone who was important to Georgie Auld's life or career. Are you an alumnus of his band, a member of his family, or a collector who is knowledgeable about his accomplishments? Please contact me via e-mail

return to "Biographical Sketches" directory

go to Big Band Library homepage

The big bands are back

in a new and exciting way!

GEORGIE AULD

"SAX APPEAL"

by Music Librarian CHRISTOPHER POPA

October 2008

After his parents gave him an alto saxophone, he would entertain guests in their family saloon.

According to a close friend, he couldn't read the printed notes on a page but was able to improvise musically after hearing only piano chords.

In 1931, Auld received some lessons from winning a scholarship named for the saxophonist Rudy Wiedoft.

A few years later, inspired by Coleman Hawkins, Auld learned the tenor saxophone.

He was able to blow the sax so excitingly that several famous leaders (namely Bunny Berigan, Artie Shaw, and Benny Goodman) invited him to join their orchestras, and Auld's full-toned playing helped to bring a new level of expression to each of those groups.

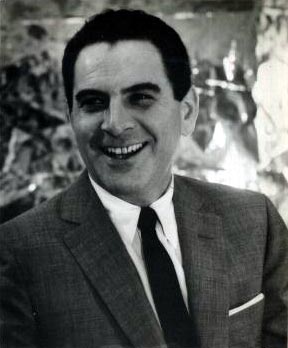

Georgie Auld, ca.1963