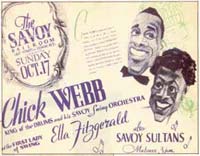

CHICK WEBB

"Stompin' At the Savoy"

by Christopher Popa August 2005

necrology - select list:

Charlie Dixon, 42?, arranger, Dec. 6, 1940

Bobby Stark, 39, trumpeter, Dec. 29, 1945

John Trueheart, 49?, guitarist - banjoist, 1949

Tommy Fulford, 44, pianist, Dec. 16, 1956

Claude Jones, 60, trombonist, Jan. 17, 1962

Elmer Williams, 57?, saxophonist - clarinetist, Jun. 1962

Moe Gale, 66?, manager of Chick Webb, Sept. 1964

Wayman Carver, 61, saxophonist - flutist, May 6, 1967

Hilton Jefferson, saxophonist, Nov. 14, 1968

Edgar Sampson, 65, arranger, Jan. 16, 1973

Louis Jordan, 66, saxophonist - vocalist, Feb. 4, 1975

Pete Clarke, saxophonist - clarinetist, Mar. 27, 1975

Taft Jordan, 66, trumpeter, Dec. 1, 1981

Charles Buchanan, 86, manager of the Savoy Ballroom, Dec. 1984

Chauncy Haughton, 80, saxophonist - clarinetist, Jul. 1, 1989

Eddie Barefield, 81, saxophonist - clarinetist - arranger, Jan. 3, 1991

Sandy Williams, 84, trombonist, Mar. 25, 1991

Garvin Bushell, 89, saxophonist - clarinetist, Oct. 31, 1991

Mario Bauza, 82, trumpeter, Jul. 11, 1993

Ella Fitzgerald, 79, vocalist, Jun. 15, 1996

Beverly Peer, 84, bassist, Jan. 16, 1997

Teddy McRae, 91, saxophonist - composer, Mar. 4, 1999

Alexander turned 90 this past May.

"I still feel well, and I'm grateful for that. I have a wonderful family. My wife and I are celebrating 66 years of marriage," he reported.

When ASCAP presented him with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2002, in his acceptance speech, he remarked that his lifetime achievement was his picking the right partner in life and having a wonderful family.

"You gotta measure success that way, too, I guess, don'tcha think?," he asked.

sources:

Alexander, Van. Interview with author, Nov. 8, 2004.

Fritts, Ron and Ken Vail. Ken Vail's Jazz Itineraries 2: Ella Fitzgerald: The Chick Webb Years

& Beyond (Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003).

Korall, Burt. Drummin' Men: The Heartbeat of Jazz, The Swing Years (New York City:

Schirmer Books, 1990)

send feedback about Chick Webb: "Stompin' At the Savoy" via e-mail

return to Biographical Sketches directory

go to Big Band Library homepage

"I guess it was about 1936. A lot of us teenagers at that time used to frequent a place in Harlem called the Savoy Ballroom and Chick was sort of the house band there," Van Alexander recalled to me recently. "And I was, at the time, interested in arranging - I was studying arranging. After going there quite a few times, I had what we call a 'nodding acquaintance' with Chick. He'd shake his head and say, 'Hi, kid.' And I'd say, "Hi, Chick.'"

"And one night, I got up a little nerve and I said, "Chick, I've got a couple of arrangements at home that might fit your band, if you're interested. Would you like to hear them?' He said, 'Sure, bring 'em down to my rehearsal a week from Friday.' Well, I was bluffing, I didn't have any arrangements [ chuckles ]. I went home and did them and I brought 'em down, and that was my introduction to Chick Webb."

vital stats:

given name: William Henry Webb

nicknames: "Chick," "King of the

Drums"

birth: Feb. 10, 1909, Baltimore, MD

death: June 16, 1939, spinal

tuberculosis

family: two sisters

wife: Sally?

initial engagement as leader: Black

Bottom Club, Manhattan, 1926

in his own words: "Music comes first."

Early in his life, Webb had been accidentally dropped on his back, smashing several vertabrae. Because of this, he became a hunchback and never fully grew. Playing drums helped to strengthen his body.

"He was a genius because of his small stature," Alexander observed. "He was a little hunchback. . . [and] . . . the people loved him."

"He didn't read music at all," Alexander pointed out. "Chick didn't read music, but all he had to do was hear an arrangement once, and he memorized it and through his own ingenious ear, he amplified what I would write.

In fact, I don't remember ever writing anything [a drum part] for him, 'cause he couldn't read."

So how did Alexander know what to write for the other instrumentalists?

"Well, I was familiar with his band. As I say, we went there to dance, but I was always listening to the great arrangements of the black bands that played at the Savoy. There were bands like Lucky Millinder and Teddy Hill [and] Willie Bryant and Erskine Hawkins," he explained. "So I was interested in the arranging. I had been studying arranging with a man in New York City by the name of Otto Cesana. I experimented in high school with a few little bands, so I just stuck my neck out and it turned out to be pretty well. Chick liked the arrangements and he paid me $10 each for them. I went home and I was on 'cloud nine,' having sold my first arrangement and realizing that that's going to be my career."

Van Alexander

at a recent Los

Angeles function

The Savoy, located at 596 Lenox Avenue near 140th Street, hosted many "battles" between the big bands. Webb's band, for instance, played against Glen Gray and the Casa Loma Orchestra, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie.

Perhaps the most famous "battle" took place on May 11, 1937, when the challenger was Benny Goodman's orchestra.

"That was quite a night. I was there that night," Alexander boasted. "The Savoy Ballroom was up on the second floor and there were so many people standing in front of the bandstand. They must have had two or three thousand people. Everybody was swinging and I thought the floor was going to collapse at one point. Thank God it never did. But it was a night to savor, it really was."

Who came out on top?

"Well, it was a toss-up," he told me. "It was really a battle of the two drummers, Gene Krupa with Benny, and Chick Webb. In later publications, Gene said, 'The little man really cut me that night.' He was honest."

recommended listening - select performances:

A-Tisket, A-Tasket voc. by Ella Fitzgerald, arr. by Van Alexander /

May 2, 1938, Decca

Blue Lou arr. by Edgar Sampson / Nov. 19, 1934, Decca

I Got Rhythm as "Chick Webb and His Little Chicks" /

Sept. 21, 1937, Decca

Who Ya Hunchin'? Aug. 18, 1938 / Decca

There's Frost On the Moon voc. by trio, arr. by Van Alexander /

Jan. 15, 1937, Decca

Go Harlem arr. by Edgar Sampson / June 2, 1936, Decca

I'll Chase the Blues Away voc. by Ella Fitzgerald /

June 12, 1935, Brunswick

Liza (All the Clouds'll Roll Away) arr. by Van Alexander /

May 3, 1938, Decca

A Little Bit Later On voc. by Ella Fitzgerald, arr. by Van Alexander /

June 2, 1936, Decca

I Can't Dance (I Got Ants in My Pants) voc. by Taft Jordan /

May 9, 1934, Columbia

Blue Minor arr. by Edgar Sampson / Jul 6, 1934, Okeh

Clap Hands! Here Comes Charlie arr. by Edgar Sampson /

Mar. 24, 1937, Decca

Everyone's Wrong But Me voc. by Ella Fitzgerald,

as "Ella Fitzgerald and Her Savoy Eight" / May 24, 1937, Decca

Harlem Congo arr. by Charlie Dixon / recorded Nov. 1, 1937, Decca

Ella Fitzgerald, at age 17, had joined the Webb band in 1935, and quickly become one of its featured performers.

"He was giving me assignments to do, mostly Ella's early Decca records. I didn't do very many instrumentals, outside of the first two things I wrote for him, Keepin' Out of Mischief Now and That's

a-Plenty," Alexander said. "He was on the air so much from the Savoy and then, later on, from Boston, where A-Tisket, A-Tasket happened. He was loading me up two and three weeks ahead. I was doing three arrangements a week for the band. He had to please the publishers -- or try to please them, anyhow -- [who tried]

. . . to get their tunes played on the air. And they were contacting him. Many times, they paid for some of the arrangements."

more arrangements

by Van Alexander

for Chick Webb, 1936 to 1938

Cryin' Mood

Crying My Heart Out for You

Devoting My Time to You

Dipsy Doodle, The

Everybody Step

F.D.R. Jones

Gee, But You're Swell

Gotta Pebble in My Shoe

Hallelujah!

I Can't Stop Lovin' You

I Found My Yellow Basket

I Got a Spring Fever Blues

I Love Each Move You Make

I Want to Be Happy

It's Swell of You

Just a Simple Melody

Love Is the Thing, So They Say

McPherson Is Rehearsin' (To Swing)

Organ Grinder's Swing

Pick Up Your Sins

Rock It for Me

Rusty Hinge

Sing Me a Swing Song

Swingin' On the Reservation

Take Another Guess

Vote for Mr. Rhythm

Wacky Dust

Wake Up and Live

You Showed Me the Way

"You know, if you listen to some of Chick's records today, some of the old records, you've got to realize that this was before stereo and reverberation and all the techniques that went into later recordings," Alexander reminded me. "So that when you listen to his records today, they're a little flat-sounding. But when you heard them in-person, they were exciting! He had five brass; that is, three trumpets and two trombones, and he used to call them 'the five horsemen.' And just four saxophones, and rhythm. When I started my band, and all the later bands -- the Glenn Millers and Goodmans and so forth -- had eight brass. You know, like four trumpets and four trombones and five saxophones. So, the later bands always sounded better to me than the Chick Webb band."

Webb had the respect of other musicians, who knew they were in for a fight when they ventured into the Savoy, which was his territory. Yet once A-Tisket, A-Tasket became a hit, he modestly turned the spotlight over to Fitzgerald.

"Chick saw the commercialism, and the applause that Ella got for the band, so he did, more or less, concentrate more on her than he did the band. You're right, there," Alexander confirmed. "He featured her, and she did guest spots with Benny Goodman... guest spots on different shows while she was still with the band. He did feature her more than the instrumentals."

But for Webb himself, the rewards didn't last long, because his health began to diminish by 1939.

"Well, shortly after A-Tisket, A-Tasket, Chick died. Unfortunately, he wasn't able to reap some of the benefits, if he had lived a little longer," Alexander said. "So, for a while, Ella took over the band, and it was Ella with the Chick Webb band. But that was, sort of, short-lived. And then it, sort of, I don't know, just dissipated. Nothing much happened with it, after that at all. And then, Ella went out on her own, and you know the story there."

"All the guys in the band," Alexander went on, "you gotta realize, I was the only, they used to call us 'ofays.' Did you ever hear that expression?"

"White person, yes," I answered.

"Did you ever hear the derivation?" he wondered. "It's pig Latin for foe, f-o-e. Not too many people know that. So I was the only 'ofay' in and around the band, outside of his manager, who was a man by the name of Moe Gale. I traveled with the band, on occasion, in the bus, and I got quite an education, I must tell you."

Did things ever become uncomfortable?

"No, not really," he claimed. "We never thought about it. It was never discussed. I must tell you, my parents weren't too happy about it. But when they saw that I had a future, they sort of came over to my side. No, but there was no... either I was not cognizant of it, or I never felt any racial divide at all. As a matter of fact, the guys were really wonderful to me, and I have some wonderful memories and pleasantries in being with the guys and having a glass of wine with them, and so forth, after rehearsals. So it was a little unusual, there's no doubt about it -- a white kid just spending so much time in Harlem. At the first rehearsal, which didn't start until after the dance session was over (the place closed up at 1 o'clock, and then the guys in the band would go and have something to eat and then a little Muskatel wine or something). And then they started the rehearsal about 2, and Edgar Sampson had an arrangement there to rehearse... and another fellow by the name of Charlie Dixon... and a baritone player in the band, his name was Wayman Carver. So, by the time they got to my arrangement, it was after 4 in the morning, and my mother called the police. She said, 'My son is in Harlem. My God, what can he be doing at 4:30 in the morning?' But [chuckles] that's the way it was."

Though he's told it many times before, Alexander kindly related, once more, the story of how A-Tisket, A-Tasket came about.

"Yes, of course, from the horse's mouth, so to speak," he quipped to me. "Chick and his band were playing in Boston, at a place called Levaggi's Restaurant. And they were broadcasting, coast-to-coast, about three or four times a week."

The engagement in the Flamingo Room at Levaggi's began on February 7, 1938.

"My assignment was to do three arrangements a week for the band, mostly Ella's things," he continued. "They were there for about five weeks at this place, and in the basement, there was a group called The Ink Spots, the first Ink Spots group. They were handled by the same manager that handled Chick and Ella. So, anyhow, one day I got to Boston, Ella says to me, 'I got a great idea for a song. Why don't you try to work up something on the old nursery rhyme A-Tisket, A-Tasket?' And I said, 'Gee, that is a great idea, Ella, lemme think about it.' Well Chick, as I said, had given me assignments for the following two weeks -- that would be six tunes -- and so I just didn't have time to think about A-Tisket, A-Tasket. She said, 'Did you think about [it]?' I said, 'I thought about it, Ella, but I just didn't have the time. The following week, the same thing happened, I didn't get to it, and this time, Ella got a little testy (which she'd never done). She said, 'Well, look, if you don't want to do it, I'll ask Edgar to do it, 'cause I think it's too good an idea to... " 'Hold the phone! I'll get to it next week, I promise ya.' Now, you gotta realize, the old nursery rhyme A-Tisket, A-Tasket was in [the] public domain. There was never really a song, it was just a little rhythm thing that the kids used to sing. What I did was to put it into form, a 32-bar song. I put the release, the bridge to it, and all the novelty things to it ('Was it red? No-no, no-no. Was it blue?' and so forth). And I brought it up to Boston, and Ella and I went over it and she changed a lot of the words. I had written, in the middle part, I said [sings] 'She was walkin' on down the avenue, without a single thing to do,' and Ella said, 'Let's say she was truckin' on down the avenue.' Not walkin, truckin', 'cause that was a big word in those days, you know. So I said, 'Yes, great!' And she changed a few other lyrics also. Well, they put it on the air that night, and somebody telephoned Robbins Music in New York and asked them to take [an acetate] off the air. And they did, and they got excited about it, and two weeks later, [the band] went to New York, to Decca Records, and recorded it -- on my birthday, incidentally -- May 2nd, 1938. It was a big hit that summer, and on the Lucky Strike 'Hit Parade,' which was the big radio program in those days, it stayed #1 for 19 weeks."

Van Alexander [ r. ] and two other great arrangers, each of whom knew Chick Webb's music. Benny Carter

[ middle ] wrote some things for him, and Billy May [ l. ] recreated three of Webb's records, including If Dreams Come True, for Time-Life's "Swing Era" series in 1970-71.

Although Alexander studied with Cesana, a classical musician, and his mother was a concert pianist, he didn't incorporate any classical sounds in his charts for Webb.

"Not really, no. They were two different things," he explained. "My mother's tuition of me at the piano was really invaluable, though I didn't realize it at the time. When all the other kids were out playing stickball or baseball, I wanted to be out playing ball, too. But thank goodnesss I stayed with it, and learned the fundamentals of the piano, and proper harmony, and how to read, and so forth, and that held me in good stead when I went into orchestrating. The classical music didn't enter into it at all. As a matter of fact, Cesana, who was a pretty serious composer, as well as a teacher, used to look at some of the scores that I did for Chick Webb, and didn't quite understand. 'Why did you do this?' he would say. 'And why did you do that?' And I explained it to him, and then I had the records of the arrangements that I did for Ella and for Chick, in the early days."

So the student was teaching the teacher.

"When it came to jazz and popular music," he agreed. "What I learned from Cesana was the full symphony orchestra - strings and woodwinds and percussion and so forth, which I used later in life when I came to California."

I asked Alexander to comment on one of his colleagues in the Webb band, fellow arranger Edgar Sampson.

"He was there before I started with the band," he said. "He was the true writer of Stompin' At the Savoy, although it came out written by Edgar Sampson, Benny Goodman, and Chick Webb, who had nothing to do with it, outside of recording it. But Edgar was a great contributor to the band, and they loved him. They had a nickname for him, called him 'the lamb' because he was so mild-mannered and gentle. He was a gentleman of the old school. And I corresponded many years later with Edgar, before he passed away, and he and I were pretty close friends."

The Alexander band recorded first for Bluebird, then, when Oberstein started his own label, Varsity, they followed him there in 1940.

"Well, unfortunately, I didn't have a real recognizable sound," Alexander said to me. "I think that was one of the reasons that we didn't break through bigger than we did. I used whatever experience I had gotten with the Chick Webb band and all the other bands -- incidentally, I had [also] worked for Lucky Millinder and for Teddy Hill and for Erskine Hawkins -- so, as I say, I just used that experience and put it in my band, and it was what I would call 'a pretty good swing band,' but it didn't have any real definition and there was no front man like Artie Shaw or Glenn Miller or Benny... I played piano in the band, and I was never very prolific at the piano. I could always make myself understood, but I used to play what they call 'an arranger's piano' (mostly chords and so forth). So we didn't have any real distinct sound, I'm sorry to say."

Clearly, however, there were some good guys in the band, including saxophonist - vocalist Butch Stone.

"Butch and I went to high school together, George Washington High School in New York City," he reminisced. "So he was in my first band in high school. So, naturally, when I started with the real big band, he was one of my first choices. I wrote a thing for him that made quite a hit... I guess you've heard... A Good Man is Hard to Find. So he was with my band for the first two-and-a-half, three years. And when we weren't getting too much work, I said, 'Butch... ' 'Cause he got inquiries from different bands that wanted -- Larry Clinton wanted to have him and Jack Teagarden wanted to have him and so forth. So he asked me if he could take the arrangement of Good Man to Larry Clinton. I said, 'Sure, you can have it. Nobody else can do it but you, anyhow.' So he took it with Larry and everyplace he went, it was a smash hit. Then he left Larry and went with Jack Teagarden, the same thing, he took the arrangement. He finally ended up with Les Brown. And Les had the foresight to record it. Why I never did, I don't know. But Les recorded it and sold a lot of records... 500... 750 thousand. We used to joke about the fact that I never got paid for the arrangement. I said, 'This thing has been kicking around now for so many years.' So Les and I played golf quite a bit out here, and one day he said to me, 'Guess what? You're gonna get paid for Good Man Is Hard to Find. I said, 'How come?' He says, 'We're gonna re-record it for [the] BASF label in Germany and they have to pay for all of the arrangements [ laughs ].' So . . . [thirty-five] . . . years later, I finally got paid for Good Man. A true story!"

Another fine musician in Alexander's band was drummer Shelly Manne.

"Shelly played with me for a short time, and we remained very good friends until the end; in fact, we're still friendly with his wife . . . and we see her out here all the time," he acknowledged. "Shelly was with me for a short time, but everybody wanted him, he was so great. But [later] he recorded with me, and I used him on a couple of pictures, whenever I could get him. And then, Irv Cottler, who later went with [Frank] Sinatra for twenty years... he was our drummer. We had a lot of good drummers."

Other personnel included, at various times, trumpeter Neal Hefti, trombonist Si Zentner, saxophonist Frank Socolow, pianist Ray Barr, and bassist Sandy Block.

"In all honesty, I had a good band, at one time. I had a lotta good players," Alexander commented. "It was never a big success, when you think of the Glenn Millers or the Harry Jameses, and so forth. We did fairly well. I played all the good spots; we played, you know, the Paramount Theatre and the whole east coast, from Maine to Florida, and as far west as Chicago. And we were all young and enjoyed it. but I sorta saw the handwriting on the wall and I wanted to try to get out to California, when I could."

That tale actually began in New York City.

"In 1943, the War was [on and] I had gotten a defense job, because I was given a deferrment because I had two children, at the time. The Capitol Theatre, during the War, was just showing pictures. They wanted to re-activate the stage band policy, and the first band they booked was Bob Crosby. But Bob didn't have a band, he had just gotten out of the service, so my manager at that time, a fellow by the name of Joe Glaser (who also managed Les Brown), he cooked up a deal where it would be Bob Crosby with the Van Alexander Orchestra. And we opened the Capitol Theatre, and we had four very nice weeks there. Bob and I hit it off pretty well, and he asked me if I wanted to think about coming out to California and putting a band together for him, and arranging and so forth. My wife . . . talked it over and we thought it was the right thing to do and the right time."

Crosby was best known for big band dixieland pieces, alongside his amiable vocals.

"Well, he had quite a few of the dixieland things, but I wrote quite a few charts for him and came out here at my own expense, and brought my family out after about 10 weeks. I wanted to make sure everything was going to be ok. And we bought a little home... borrowed everything I could to do that," Alexander reminisced. "Then Bob and I had a big fight, and he fired me

[ laughs ]. And I was out here, high and dry, with my family, and I may have established a little reputation in the East, but nobody knew me out here, so I had to start a new career at age 29 or 30, whatever I was. And luckily... I say 'luckily' because I got my feet wet in television. An old songplugger, a friend of mine -- who's now managing Mickey Rooney, who was in one of his career lulls... you know, he was so big at one time, and now, he's just struggling a little bit -- and he got a television show, and his friend, who's managing him, hired me to do the music. And that was just the start of a great television career for me, 'cause I branched out and did a lot of the big shows that are still being shown here, like many, many segments of 'Bewitched' and 'I Dream of Jeannie' and 'Hazel' and all the shows at Screen Gems. And through them (Screen Gems was a subsidiary of Columbia Pictures) . . . I got to do a couple pictures at Columbia, and I've worked at every studio out here. I did about twenty-two full-length pictures... no Academy Awards, but they were all good credits and are still being played, you know, on late-night television throughout the world."

At the end of his life, Webb was in John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, MD. It was said that he was at death's door for two or three days, but was fighting bravely. When his passing became inevitable, he was said to have asked his mother to raise him up. He faced the relatives and close friends in the room, announcing "I'm sorry I got to go!" and died then and there.

vital stats:

given name: Alexander Van Vliet Feldman

birth: May 2, 1915, New York City

father: pharmacist

mother: concert pianist

musical training: with Otto Cesana; Mario Castlenuovo-Tedesco; a few

extension courses at Columbia University

wife: Beth, m.1938

children: two daughters

grandchildren: four

memberships: Past President, American Society of Music Arrangers

and Composers (ASMAC); Executive Board, Big Band Society of

America; member, ASCAP, 1941- ; member, Music branch of the

Motion Picture Academy

hobbies: golf

It was not Chick's death that motivated Alexander to start his own orchestra.

"No, no, that's another story," he said. "There was a fellow by the name of Eli Oberstein. He was the head of RCA Victor Records. He had established what he called a 'stable' of songwriting bandleaders: he had signed Larry Clinton, and he signed Les Brown, and after Tisket

A-Tasket, he thought he had another one. He made me a deal to come into his stable, so to speak."

The year was 1938, and the first order of business was to change his name.

He had been named Alexander Van Vliet, after his grandfather, and Feldman was his last name at birth.

"So Oberstein says, 'Well, why don't we take the 'Van' and the 'Alexander' which was your name and...' And I said, 'Well, if you think that's [an] important thing to do.' And so we went to court and had my name changed," Alexander explained. "But they never changed it on the sheet music, a little to my chagrin. As a matter of fact, when Ella did the public television thing (PBS), they showed the record, A-Tisket, A-Tasket, and on the original 78, it says Ella Fitzgerald and Al Feldman. But my ASCAP statements have all been changed, and since 1938 I've been, legally, 'Van Alexander.'"

Next, he had to choose a theme song.

"Originally, when I started, I used Alexander's Ragtime Band, which was a natural for me. But when I started to do it on the air, I got a crease-and-desist telegram from Irving Berlin's publishing company, that he didn't want anybody associated with that song, except himself," Alexander revealed. "So I had to write another theme, which I called it Alexander's Swinging, and I was never really happy with that, either, but it served its purpose for when I was on the air."

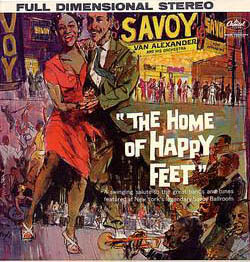

Back in New York City, the Savoy Ballroom closed in 1958, and not long afterwards, came an idea to do a recorded salute to some of the great bands and tunes that had been featured there.

"They have what they call a&r men, standing for artists and repertoire. And one of the fellows, his name was Dave Cavanaugh; you may have seen his name on certain things. It was his idea," Alexander remembered. "He said, 'Geez, with your association at the Savoy Ballroom, why don't you do an album, using your memory as to what these things sounded like, and do 'em with a studio band. Sort of re-creations of what they were. But, in many cases, they're so much better than the originals were. So that's what we did."

Of course, A-Tisket, A-Tasket was included.

"It's the same arrangement, actually, that Ella sang, except, as I mentioned before, my albums were eight brass and five saxes, and we had stereo and reverb, and it sounded so much more alive than the original thing," Alexander noted. "But Ella's record is still being played, and I'm just grateful and lucky that I found the time to do it, 'cause it could've been done by Edgar."

Alexander is also the author of an instructional guide called First Arrangement, to help young people entering the business.

"Arranging, actually, is a bit of composition," he remarked. "When you write an introduction to an arrangement, or a special ending, or a special interlude, you are composing. I also said that a lot of people are in the dark as to what does an arranger do... I mean, what is his main function? And I said that an arranger is a songwriter's best friend, because a good arranger can take a song and re-arrange it four or five different ways for four or five different bands, and, by using different colors and different instruments and different sounds, make it more attractive. And then, many times, was the difference between a hit record and one that didn't hit."

Would Alexander have like to arrange more instrumentals, or did he prefer doing the vocal charts?

"Well, that was what Chick wanted me to do," he said. "The old fellows were doing more of the instrumental things for the band, and I was happy to just work with Ella."

With the success of "The Home of Happy Feet," Capitol requested another album from Alexander, "Swing Staged for Stereo," which, along with Cavanaugh, was produced by Tom Morgan.

"Well, that was from another a&r man, his idea. He and I collaborated on this; we did a series of duets, all accompanied by the big swinging band," Alexander said. "You know, there was a thing by two trumpets, and then there were two trombones, and two tenors, and two clarinets, and two pianos, and two drums (we had Irv Cottler and Milt Holland, and I think Shelly was on one of the sessions). And this turned out to be a great album; it's still being played. I don't know how much it sold, but, artistically I was very happy with it. All it is, though, is some of these big tunes... Get Me to the Church On Time... but all duets, with great players, with a big swinging band in the background. It was a good idea, I thought."

Another Capitol LP which Alexander conducted for was the "Jazz Singer," with Kay Starr.

"Yes, of course. I did five albums with Kay. It was very pleasant 'cause she's a great gal, and she was a great singer. We still see Kay, on occasion," he mentioned. "And, of course, I did thirteen albums with Gordon MacRae . . . and a couple with Jack Teagarden, and Dakota Staton. And then we did a series of operettas with Dorothy Kirsten and Gordon, and the Roger Wagner Chorale . . . whatever the job called for. I've got to say some of the things that I did with Gordon were, artistically, my favorites. And they weren't necessarily jazz things. There are a lot of good jazz writers around, you know: there's Sammy Nestico, and there's Neal Hefti. First of all, they're a lot younger than I am [ laughs ] but I wouldn't put myself in their class, when it comes to jazz, out-and-out jazz, there's a lot of guys that do it better than I do. I love Sam Nestico, anything he does. And there's a fellow out here, by the name of Bob Florence. I listen to a lot of classics, too. They're a lot more restful sometimes, just listen to the masters. I always wanted to, some day, write something symphonic and the closest thing I got, when Stan Kenton had his Neophonic Symphony, do you remember those days? But it's a little late for me, 'cause I can't sit that long and write anymore. But the things with Gordon are just beautiful, beautiful arrangements, and he had a glorious voice. So... it's been a pretty good ride, Christopher, and I'm grateful for it."

Happilly, Alexander has received recognition for his accomplishments. He was nominated for an Emmy three times, and was honored by the Pacific Pioneer Broadcasters and the Los Angeles Jazz Society.

"The piece-de-resistance was in 1986, almost 50 years later, the Chick Webb record and Ella and myself were elected to the Grammy Hall of Fame," he commented. "They gave me a big plaque, which is hanging on my wall. Of course, Chick had passed away by that time, his estate got it. It was quite an honor and, to this day, A-Tisker, A-Tasket is still being recorded. We had three or four new records on it the last two years: Manhattan Transfer did it, and Patti Austin did a great record of it, and DeeDee Bridgewater, and Mandy Patinkin. It's continually being

re-recorded for the new generation of kids."

Are there any new projects in the works for Alexander himself?

"I thought I had retired undefeated [ chuckles ], but I got a call from a young man just a couple months back . . . Michael Feinstein. Well, he was going in to his debut at Carnegie Hall, and he had an idea that he wanted to do a big segment of his program about big standard band tunes that all had lyrics . . . So I said, 'Well, that's a great idea, Michael, but [way before] you were a young boy, in 1938, the first jazz that was ever played at Carnegie Hall was with Benny Goodman, and he had the big success [there].' I said, 'Why don't you do a medley of tunes that were associated with Benny, they all have lyrics, and you'd have a good hook there.' And he said, 'Well, that's a great idea.' So he says, 'I'd like you to do it for me.' Well, I'm kind of flattered. And he says, 'I was talking with your first pupil, Johnny Mandel . . . and he says, "If you're going to do a Benny Goodman thing, nobody can do it better than Van Alexander."' It was such a pleasant thing, since, as I said, I thought I had retired. I hadn't done anything since 'The Dean Martin Show,' which was another 6... 7 years of wonderful music for me."

"There's no place for young arrangers to get started today, like I did," he lamented. "If you can't get to hear what you write, that's a big learning device, just to be able to hear what you write. So today, it's mostly electric guitars and synthesizers and drum machines. Everything is done on computer, and it's a different world. Anybody that's starting out in music today -- I wouldn't say anybody -- but the majority are not very well-studied musicians, because you don't need it. They become multi-millionaires by playing a record of Deep Purple with all the wrong chords and... you know what I mean? It's very frustrating, too. So, the arranger, as we know it -- and there are still a few of us around, not necessarily working -- has become sort of a dinosaur, really, with the exception of picture scores. Every television show used to have music behind it. Now, there's play-ons or play-offs with a guitar or one piano, and it's just a different business. Everything is money -- money, budget -- but I guess that's progress, I don't know."

The big bands are back

in a new and exciting way